Articles

PLANNING OUR LIFE AND BEYOND

On average, we have only about nine decades to achieve our life goals. Whatever our age now, there is no time to waste in making the right choices.

When we at Sicart engage with clients in planning for the management, use and disposition of their fortunes, we first try to spend ample time on defining the kind of life they want to live, the goals they hope to achieve, and what legacy they wish to leave behind. Whatever the age of the clients, their views on these subjects are usually vague – probably because decisions about them do not seem urgent and are expected to come into proper focus as they age. Yet procrastination is not an option for any of us.

OUR LIFE IN MONTHS

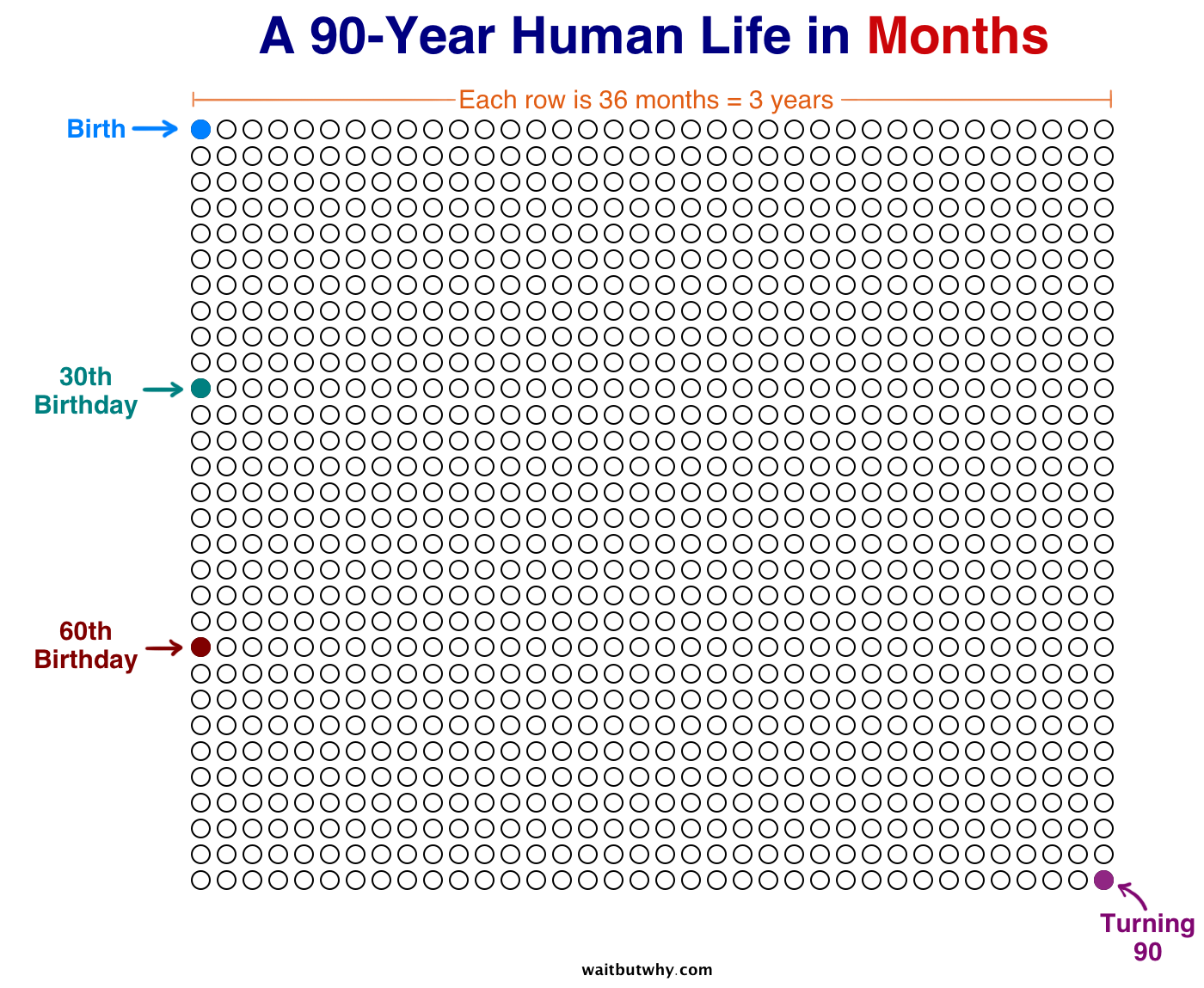

I recently came across a somewhat quirky website named “WaitButWhy.com”. One article was illustrated by pictures of the average human life expressed in weeks, months and years, such as the following:

The reminder that the average life span is just 1080 months brought to mind a memorable meeting I had with Dr. Leon Danco, whose 2013 eulogy in Forbes magazine included the following praise:

“Considered the nation’s foremost authority on family-owned business and privately-held companies, Dr. Danco was a pioneer in this field… He was a speaker, consultant and author of many books on this subject… But, he is most well-known for his sage mentorship of families and individuals, instilling in them the importance of a transformative principle: take care of the family business, as well as ‘the business of the family.’”

When I was introduced to him by a common friend around the time when I created Tocqueville Asset Management, Leon Danco had already built a highly successful career counseling owners of large family-owned businesses and, in fact, had decided to retire. When I asked how he planned to spend his retirement, he answered, “meeting people like you.” He kept me all day and never charged me for a uniquely enlightening session. Dr. Danco’s principles are explained his book Beyond Survival: A Guide for Business Owners and Their Families (published in 2003 by The Business Family Centre). For me, one of Dr. Danco’s most important points is that “a lifetime, even one that’s longer than average, is at most only 1000 months long.”

I learned a great deal from that book and will borrow here many of its ideas. One of the most important is that slicing a lifetime into a limited supply of months puts it in a very different perspective and infuses a new sense of urgency into life-long planning.

BEYOND SURVIVAL: LEARNING, DOING, TEACHING

In our first 300 months — “the learning years,” according to Dr. Danco — we learn and we consume: our contribution to society, other than giving joy to our parents, is fairly minimal.

At some point around our 25th birthday, our education in the formal sense is completed and we begin to do things. We experience successes and failures. We may abandon some endeavors and embark on new ones. Whatever contribution most of us make in our lives, we do it during our productive years. By age 50, most of our accomplishments are apparent and we are about to enter our last contributory 300 months.

Because a new generation is born every 25 years or so, lifetimes overlap: the parents are doing while the kids are learning. For Leon Danco, who was primarily concerned with the survival of the business within the family, there must be a third phase in the life of an entrepreneur: the teaching years.

I personally know at least two family business groups that have survived and evolved for several generations, though often by changing the nature of the original business and also by combining talents from within and without the family. A solid formal education can prepare children to manage, but not necessarily to lead. Leadership implies passion, which often drives entrepreneurs but not always their heirs. Furthermore, an organization’s survival depends on its culture, which in the typical case was informed by early leaders but may prove hard to maintain as the organization grows and diversifies. This is why I am not thoroughly convinced that an owner’s children should be destined to take over the family business. Still, our duty to teach, I believe, remains essential.

The notion of organizing one’s existence around three progressive phases — learning, doing and teaching — can be helpful in guiding most of our life’s important decisions. Furthermore, the realization that our doing life probably is not much more than 400 months should keep us from wasting precious time.

BEYOND ENOUGH: THE GREATER HUNGER

Even with appropriate precautions, I could not illustrate such sensitive subjects by using client families’ stories as examples, so I will share my own story, with an additional reference to another enlightening book: The Hungry Spirit by Charles Handy (1997, Broadway Books).

A social commentator and philosopher specializing in organizational behavior and management cultures, Handy was successfully an oil executive, an economist and a professor at the London Business School. He reminds us that in Africa, they say that there are two hungers: the lesser hunger and the greater hunger. The lesser hunger is for the life-sustaining goods and services, and the money to pay for them, which we all need. The greater hunger is for some understanding of what that life is for — the kind of fulfillment it can bring us beyond simply “more.”

In our modern societies, we tend to assume that fulfillment and success come from satisfying the lesser hunger. However, Handy suggests that the greater hunger is not just an extension of the lesser hunger, but something completely different. At one point in our lives, we should have enough, whatever that means for each of us: the necessities of a comfortable life and perhaps a little extra. Everyone’s “enough” is different but once we have enough, more will not make us happier.

GETTING PERSONAL

My own reflection started a few years ago. I had enough and had achieved some reasonable success during my productive years. I still felt ambition, but for a different kind of achievement.

Despite its commercial success, I had never considered the enterprise I had founded to be primarily a business. Rather, I viewed it as a profession, where financial results were secondary to the relationships with our clients and their satisfaction with our investment management and other services. Of course, I fully expected growth and profits to result from our clients’ satisfaction, but they were not the immediate goal.

Since, at this reflective moment, I had entered my teaching years (and I believed that dynastic businesses succeed only exceptionally) I had to decide whom I should teach to and what I should teach them. At the same time, I wanted to ensure that my own family would be protected and taken care of if anything happened to me, just as we had committed to do for our long-time client families.

Over the years, I had become convinced that this could be best achieved by a small team of talented and dedicated individuals, rather than by a substantial organization. This is why I picked three individuals who had exhibited their potential in the service of my long-time clients and invited them to become my partners in Sicart Associates, a highly-dedicated family office in the service of my family and a few very close others. This, I believed, would take care of my teaching years and preserve for several generations our culture of service which, together with the continued success of my professional “heirs,” would become my legacy.

[My own “dynastic” heirs are still in their doing years, with their own achievements and life goals, and I presume they feel safer knowing that their family office stands by their side. For my part, witnessing the life principles that they have adopted, I am satisfied with them as my moral legacy.]

HURRY CALMLY – THERE’S ALWAYS TIME TO DO SOMETHING WORTHWHILE

The whole point of this paper has been that, whatever our age, it is essential to plan for the rest of our lives. Even if we have missed or wasted some of our earlier stages, we can still imagine the future, select goals and consider our legacy. In doing so, measuring our lifetime and what is left of it in months should help put what we wish and what can be achieved into clearer focus.

François Sicart

July 10, 2018

Disclosure:

This article is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.