Beyond The Headlines

Always the Wrong Question

One of these days, after a spectacular decade of progress, the stock market will encounter a serious air pocket. The investing crowd will then ask the perennial question: “What caused the market collapse yesterday?” But, as usual, this will be the wrong question. The intelligent inquiry would really be: “Why did the market rise so much before yesterday’s crash?”

The Minsky Hypothesis

Over the years, I have become increasingly attracted by what is called the “Hyman Minsky hypothesis” and have referred to it in several papers. Hyman Minsky was a professor of economics at Washington University and a distinguished scholar at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. His theory was that economic “stability breeds instability:” as people feel good about current economic prospects, they tend to consume more, take on more debt, and, increasingly, speculate.

The idea that stable economies sow the seeds of their own destruction — and that this is just the nature of free markets — sounded a bit too Marxist for the western economic establishment, and Minsky was not particularly popular until the financial crisis, and Great Recession of 2007-2009 seemed to vindicate his views.

What intrigues me most about the hypothesis is that it implies that financial crises and economic recessions need not be prompted by a specific, immediate trigger. Rather, instability builds slowly but steadily as economic actors and investors are lured by apparent stability or momentum into undertaking more financial leverage (debt) and accepting (or ignoring) more risk. In doing so, they are often abetted by so-called “experts” who are best at rationalizing what people want to hear.

The Case of the 1970s’ Inflation

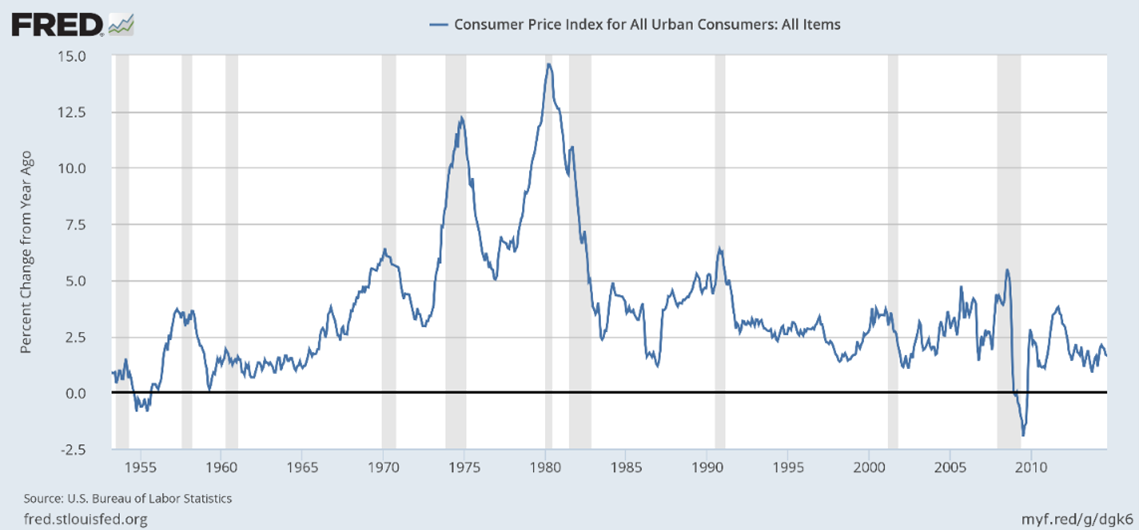

The mid-1970s are remembered as a period of double-digit price inflation, followed by the first severe recession of the postwar era. The recent uptick in prices and interest rates has revived curiosity about that period, which was followed by a stock market decline of over 45% (as measured by the Dow Jones Industrial Average between January 1973 and December 1974).

Experts of the day were prepared to find multiple causes for the accelerating inflation that continued into the next decade (after a recession-induced pause in the early 1970s). One was the collapse of the Bretton Woods system and Nixon’s shock devaluation of the dollar under the Smithsonian Agreement; another was the 1971 abandonment of the gold standard followed by the quantum increase in the price of oil after OPEC’s oil embargo (1973).

However, the following chart illustrates that inflation had clearly begun to accelerate years earlier, in the mid-to-late 1960s. In fact, it could be argued that the later developments were perhaps the result of rising inflation and its corollary – the depreciating purchasing power of the US dollar.

A Wall Street Flashback to the 1960s

If inflation actually appeared before these supposed “trigger” events, some explanation can probably be found in instability that had slowly built up in prior years, as Minsky had foreseen. And the 1960s, which are now often referred to as the “Go-Go Years,” were indeed rife with ample liquidity, mounting financial leverage, and speculation. According to the SEC, assets of stock mutual funds doubled in the five years from 1960 to 1965 and doubled again from 1965 to 1970, peaking at $56 billion in 1972. (ICI Securities Law Procedures Conference, Washington, D.C. – 1997)

John Brooks’ The Go-Go Years (Wiley Investment Classics, 1999) tells “the story of the growth stocks of the 1960s and how their meteoric rise caused a multitude of small investors to thrive until the market crashed devastatingly in the 1970s. It was a time when greed drove the market, and fast money was being made and lost as the ‘go-go’ stocks surged and plunged.” (From the book’s flap copy)

One example gives a feeling for the atmosphere of the 1960s. Investors Overseas Services, Ltd. (IOS) was founded in 1955 by financier Bernard Cornfeld. By the 1960s, it employed 25,000 people who sold 18 different mutual funds door-to-door all over Europe. In the following decade, the company raised $2.5 billion, due in part to its “Fund of Funds,” which invested in shares of other IOS offerings. Though popular, the Fund of Funds eventually turned into a Ponzi-type operation, paying investors promised dividends from newly-raised capital. After efforts at refinancing and a bailout from another troubled financier, Robert Vesco (who utilized IOS money to bail out his own ventures), IOS went out of business. Cornfeld was tried and acquitted, and Vesco fled to Havana.

To put into perspective the size of these ancient events, $1 billion in 1960 would have been the equivalent of $9.4 billion in today’s dollars. When I joined Wall Street in 1969, the New York Stock Exchange traded about 12 million shares on a good day. Even this kind of volume was overwhelming for the existing infrastructure and forced the NYSE to restrict trading to four days a week. (In comparison, today’s technology and logistics allow for a daily trading volume that approaches and often exceeds one billion shares.)

To understand how the apparent stability of the 1960s fed the instability of the 1970s, it should also be remembered that, except for cyclical slowdowns and minor or short-lived recessions, the post-war economy had experienced a long period of growth and stability. The economic establishment became complacent as a result, with several popular economists actually claiming that we had conquered the economic cycle. One of the few contrarians was Paul Volcker, who was then President of the New York Federal Reserve before becoming Chairman of the whole Federal Reserve System. Volcker had become concerned very early with the inflationary trends inflamed by the “guns and butter” economic policies of President Lyndon Johnson and his successors throughout the Vietnam war years.

Experts Always Rationalize the Recent Past and Project it Into the Indefinite Future

Amidst this complacency, a recession hit the United States in 1970. The stock market, as measured by the S&P 500 index, fell 35%. However, the overall economic recession was relatively modest and, importantly, was mostly domestic in nature. Experts, in particular from the largest wealth management banks, were prompt to concoct a new investment theme. Noticing that a number of companies had survived the recession and the stock market declined relatively well, they started promoting investment in the so-called “Nifty Fifty,” arguing that these recession-resistant stocks could be bought and held forever, regardless of the price. (Source: USA Today, 4/1/2014)

Post Mortem: In the 694 days between January 11, January 11, 1973, and December, December 6 1974, the Dow Jones Industrial Average benchmark lost over 45% of its value, but the Nifty Fifty stocks fell even further. The market, as measured by the Dow Jones Average, did not recapture its 1973 high until the early 1980s. Many of the Nifty Fifty took much longer to recover, while some never did.

Fast Forward to 2022

The fundamental question facing investors today is whether the current acceleration of inflation will be “transitory,” as the Fed seemed to believe until recently, or more sustained, as skeptical economists have argued. Personally, I tend to see inflation as a trend that is not easily halted or reversed. But, in periods like the current one, I tend to revert toward the Minsky view of the world.

Greed, risk-taking, and speculation are not easy to measure. Equally, the level at which exuberance becomes intolerably irrational is subtle. These attitudes usually announce themselves by a series of anecdotes rather than by concrete data. Still, the anecdotes are now accumulating – slowly but increasingly difficult to ignore. As usual, they seem to be rationalized by self-anointed “experts.”

Consistent with their past record, growing numbers of strategists, asset-allocators and wealth managers have joined the FOMO crowd, feeding their clients’ “Fear Of Missing Out.”

For a while, with interest rates close to zero, the philosophy became TINA – “There Is No Alternative” (to equities, i.e., the stock market). Then, as the US stock market was irrepressibly carried higher by a handful of very successful, though very expensive companies, the FAANG stocks (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google) came to the fore. They could be considered the modern-day version of the 1970s Nifty Fifty.

More recently, investment experts have steered their clients to more exotic “alternative” investments: private equity, private credit, etc. One of the main attractions here is that, contrary to the structure of the stock market, precise valuations are unavailable or hard to fathom in the near term. This situation promotes the promise of better eventual returns as a trade-off for the lack of liquidity in the near term – a splendid way to tie up investing clients’ funds.

Money has been diverted to assets such as real estate, art, wine, etc., increasingly fusing investment greed and lifestyle aspirations. But then, the internet took over from the experts. Now, websites and chatrooms promote products such as cryptocurrencies, NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens, or digital pictures of an original product), memes of fashionable stock tips, etc. Most of these new products attract millions of small, inexperienced investors, but, occasionally, they are also endorsed by investing stars, who know how to capitalize on a new trend when they see one.

If you still doubt that there is too much money sloshing around and getting “invested” mindlessly, just read this recent headline:

January 8, 2022

A reality star who says she made $200K from selling her farts in Mason jars is pivoting to selling them as NFTs

On pornographic grounds, one might understand the idea of paying real money for the packaged farts of a sexy influencer. But pictures of the jars???

The Rewards of Being an Early Skeptic

Bernard Baruch (1870-1965), the famed speculator whom historian Thomas A. Krueger described as one of the country’s richest and most powerful men for half a century, famously said:

“I made my money by selling too soon.”

Times like now seem like good ones to emulate his investing style…

François Sicart – January 12, 2022

Disclosure:

The information provided in this article represents the opinions of Sicart Associates, LLC (“Sicart”) and is expressed as of the date hereof and is subject to change. Sicart assumes no obligation to update or otherwise revise our opinions or this article. The observations and views expressed herein may be changed by Sicart at any time without notice.

This article is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.