Beyond The Headlines

As Adam Said To Eve, The Great Transition – 30 Years Later

Back in June of 1993, I wrote for Tocqueville Asset Management (the firm that I had created in 1985) a short paper entitled “As Adam Said to Eve.” The somewhat tongue-in-cheek title announced a major transition in the post-WWII world order. Until that point in the 1990s, the global system had been led and controlled by the United States, and that was slowly changing.

In my paper, I pointed out that serious economists and historians are prone to claiming that we are in a period of transition. Today, after several recent economic accelerations and slowdowns, this prediction seems to be gaining momentum again. We may, in fact, be in phase two of the Great Transition announced 30 years ago.

US leadership and the beginning of globalization

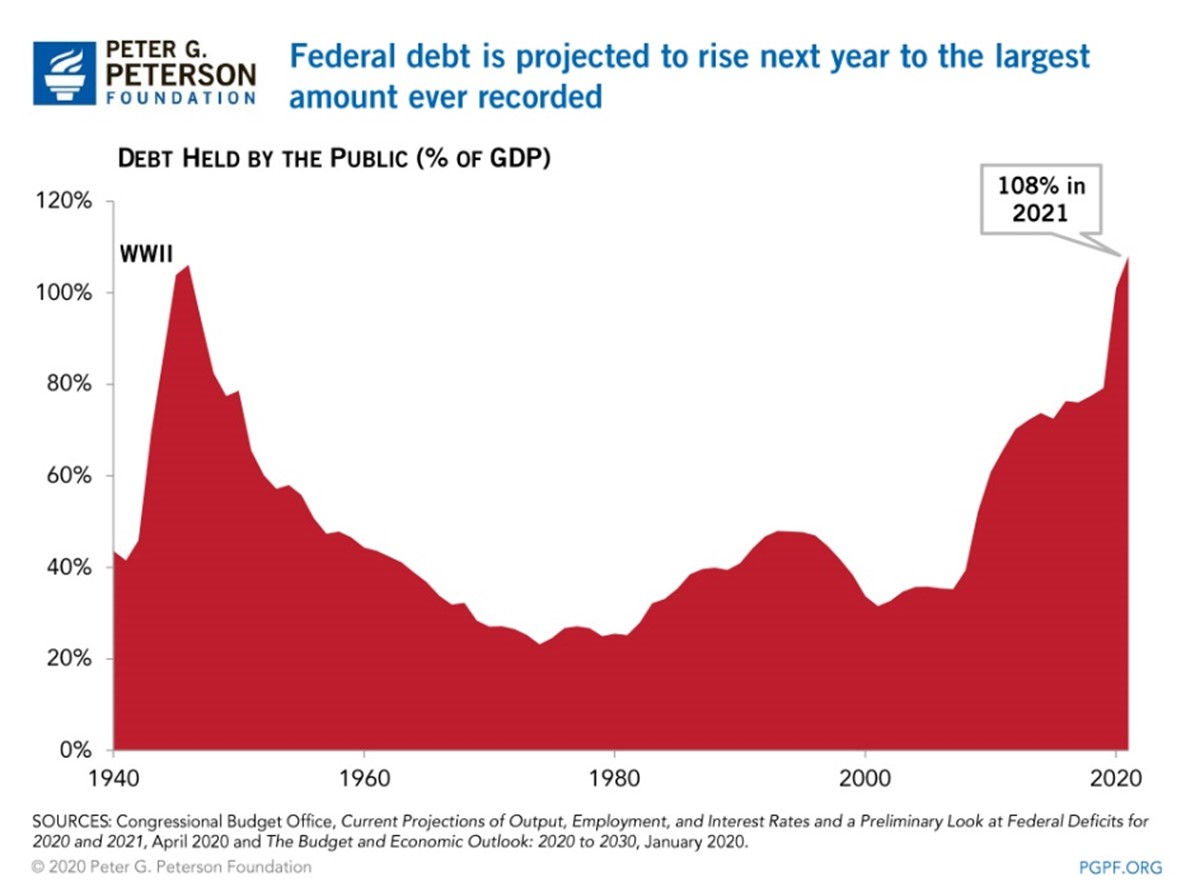

Since the end of WWII, the United States has fulfilled the leadership role of “lender of last resort,” as described by Charles P. Kindleberger in his treatise on The World in Depression – 1929-1939. The U.S. also played the role of buyer of last resort for the world, as was made plain by an increasingly large balance-of-trade deficit with struggling or developing economies. This deficit was counterbalanced by a large inflow of capital, taking advantage of America’s “exorbitant privilege” of being able to print the U.S. dollar at will. This permitted the dollar to become the de-facto world currency. Jacques Rueff, the adviser to French President de Gaulle, initially pointed out and criticized this privilege and thus prompted the abandonment of the link between the US dollar and gold.

Early globalization of the world economy under American leadership allowed other countries, largely European, to rebuild after World War II. Another result was the development of newer economies across the globe. The system was neither perfect nor intended to be eternal, but certainly, in those years, many nations grew and prospered. Little by little, however, they began to desire more independence and initiative while the United States gradually realized the burden and economic cost of its global responsibilities.

From free markets to neo-protectionism

More recently, as pointed out by The Economist magazine (1/12/2023), “President Biden’s abandonment of free-market rules for an aggressive industrial policy has dealt (the old order) a fresh blow.” This transformation — which alert observers could have seen coming — was sharply accelerated by the COVID pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war, and the resulting supply-chain disruptions. The vulnerabilities of an increasingly-integrated world economy were clearly exposed.

And the US is not alone; this new protectionism is spreading throughout the world. One result is that more nations thrive to protect themselves from foreign competitors by penalizing imports. Another is the effort to ensure the national production of essential resources, products, or technologies that had been previously sourced from the cheapest or fastest producers, regardless of location. As a result, we expect to see misallocated capital, periodic excess supplies, and probably greater-than-optimal costs for some products. Those factors will prompt slower growth in both revenues and profits for most economies and several industries.

How do we investors protect ourselves

First, in spite of the slower growth trend of various economies, I doubt that most central banks’ goal of 2% inflation can be durably achieved because it implies the acceptance by populations of unbearable amounts of pain. Even a 2% inflation rate implies a 22% loss of purchasing power in just ten years, while a 4% inflation would mean a near-50% impoverishment. Secondly, the misallocation of capital from rushed investment programs implies periodic oversupplies of individual products and commodities. This may not affect the long-term trend of inflation, but could depress profits over shorter periods. It may thus be prudent to avoid industries where investment is dictated by government policy rather than the traditional profit motive.

40 years of declining interest rates

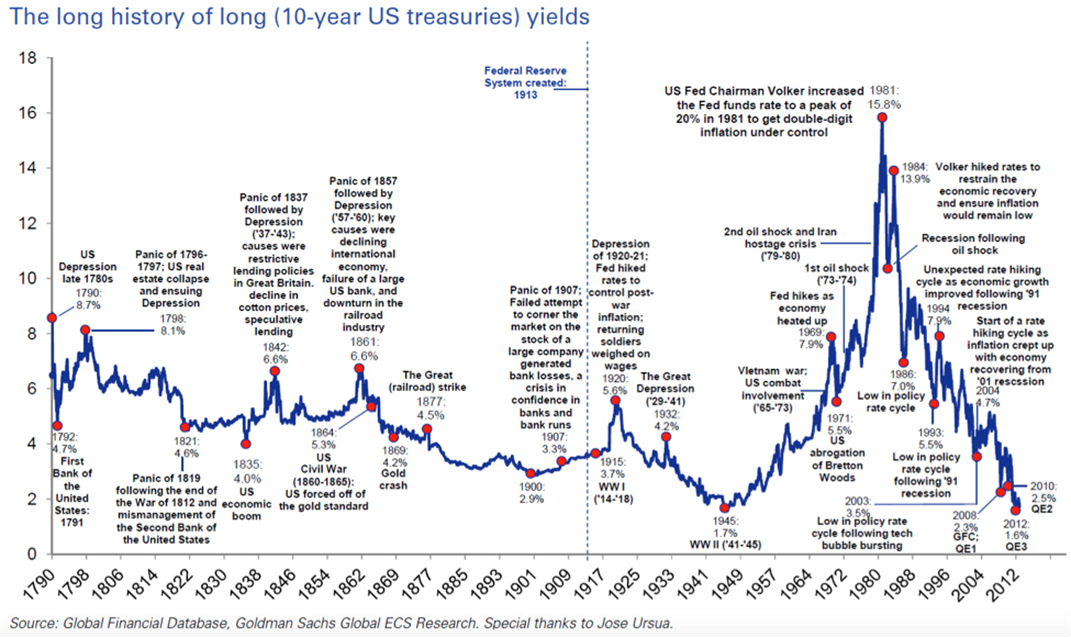

The above chart depicting the long-term history of interest rates in the United States is interesting from two points of view. First, it illustrates that, before the creation of the Federal Reserve, interest rates were relatively stable on a declining trend. Since the creation of the U.S. central bank, they have become more volatile, subject to spikes during inflationary episodes (such as the 1960s and 1970s) and – since the early 1980s — on an unprecedented downtrend, which recently culminated with a very low-to-negative cost of money.

Perhaps this is due to the fact that, in the earlier period, interest rates were more influenced by the external behavior of gold and the dollar, which were theoretically linked — whereas more recently, interest rates have depended on the human (not to say political) decisions of a board ironically entrusted to eliminate the cyclical vagaries of the economy.

Separately from this observation, it is interesting to reflect on the impact of the 40-year decline in the cost of money, which has accelerated sharply since the Great Recession of 2008-2009. This long decline has had a profound effect on the behavior of consumers, businesses, and investors. I have often referred to Hyman Minsky’s hypothesis that (economic and financial) stability eventually feeds instability by fostering the acceptance of risk, financial leverage (debt), and speculation.

It could be argued that the recent years hardly constitute an example of economic stability. Yet major economies – especially that of the United States – have survived and often experienced steady employment and subdued inflation. These two statistical phenomena could be interpreted as a form of stability.

More importantly, we believe negligible interest rates and central bank-induced ample liquidity have promoted increasingly speculative activities and behaviors. This phenomenon has ranged from faster IPOs (initial public offerings) of companies that still offer more promises than earnings, to SPACs (blank-check companies), to cryptocurrencies and related activities, and finally to small investors’ speculative mob- or meme-centered stock market gyrations. Not surprisingly, this speculative boom has been accompanied by an increase in fraudulent and Ponzi-like schemes.

How do we protect ourselves as investors?

Walter Mewing, one of my most influential mentors and a financial analyst, warned me that sometimes companies with minimal earnings may nevertheless sustain their price because their stocks are selling on the basis of dreams. When they start earning money, however, their prices may weaken because they will be bought on the realistic basis of a calculated value reflecting those earnings.

In light of this advice, one of my reservations about the behavior of the stock market over the last 20 years is that the companies presenting themselves as “disruptors” of industries (from technology to sales and distribution) are trying to convince that boosting sales very fast will allow them to garner a commanding share of their target market. Then, theoretically, profits will follow once the expenses from swift investment and massive personnel hiring are covered by growing revenues. Some of these potential “disruptors” are projecting dreams that seem credible in an era of costless capital, but issues may appear when interest rates rise, or plentiful liquidity evaporates.

The market and the economy

In periods of crisis (actual or expected) central banks have a tendency to provide more liquidity than the physical economy can absorb. As a result, the excess liquidity tends to flow over to the financial markets.

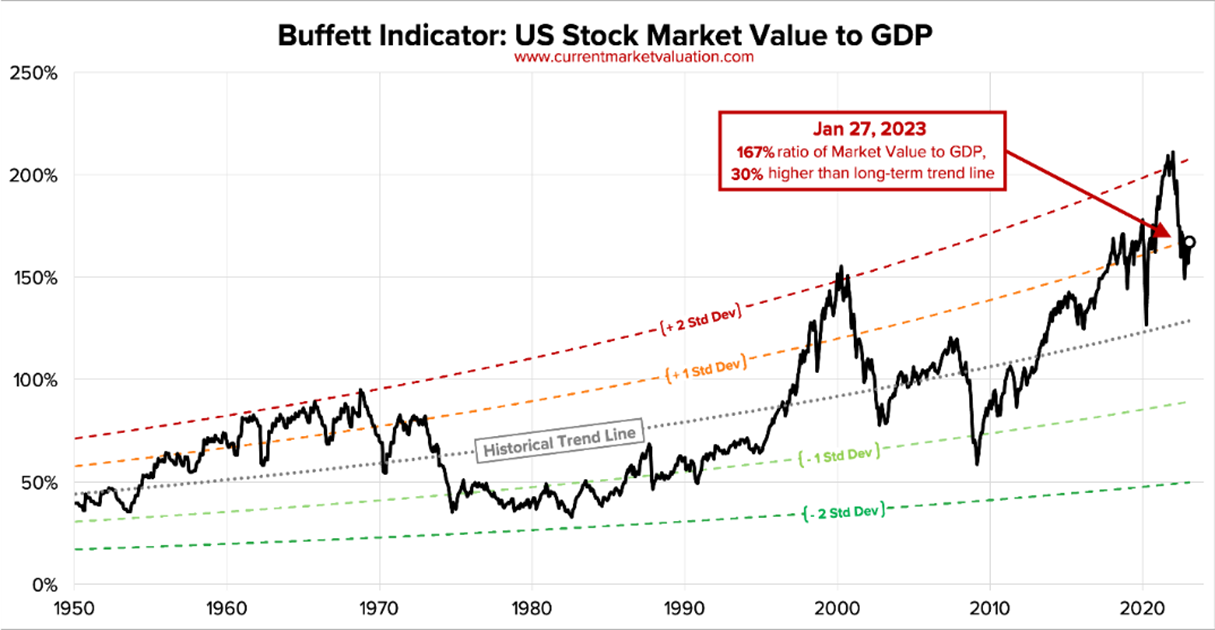

The following chart depicts one of Warren Buffett’s preferred measures of value in the US stock market. It compares the total value of the 5,000-odd companies in the Wilshire 5000 index (most of the US-listed companies) to the size of the US GDP. As can be seen, US stocks became overvalued in the late 1960s-early 1970s inflation, in the early 2000s’ dot-com boom, and even more so in 2022, before the recent retreat. As a result, in the past twenty or thirty years, the share of the population with savings invested in the stock market has become increasingly rich. Meanwhile, the rest of the population saw their incomes stagnate or fail to keep up with even the subdued cost of living.

How to protect ourselves as investors

According to the chart, even after the recent correction the US stock market may still be 30% overvalued. Thus, it may be prudent to avoid recent favorites that have driven the stock market indexes to new highs.

The question of the dollar

Currency fluctuations are particularly difficult to anticipate. In a relatively free-trading world, when the currency was a main factor of competitiveness for businesses, I used to monitor corporations to detect the point at which their leaders claimed that the overvaluation of their main trading currency necessitated a change in their production or sourcing profile. Today, when geopolitical considerations dictate government industrial policy decisions and incentives, the pure profit motive has become less obvious.

How to protect ourselves as investors

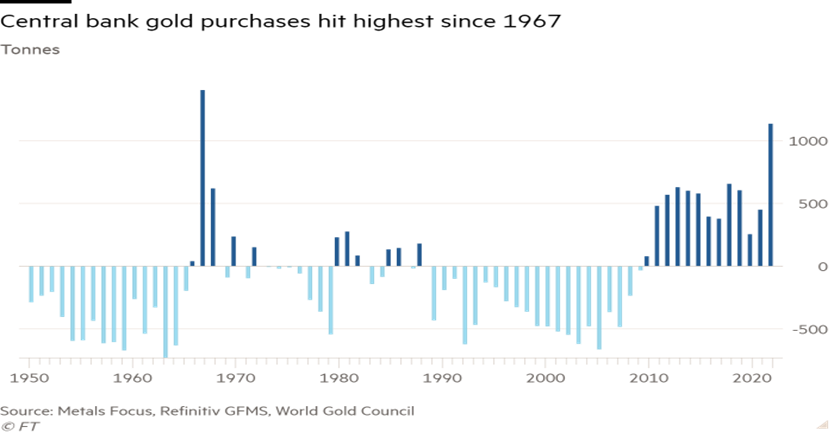

In a world where unpredictable geopolitical dislocations increase, businesses and investors tend to seek havens from currency gyrations. In recent years, it seems that many have looked for refuge in the US dollar, which, until very recently, had been steadily rising against other currencies. Now, however, many governments are unnerved by the unpredictability of American political and economic policies. This sentiment has been reflected in a new appetite for gold.

The social/political pendulum

The last 30-odd years have evidenced a growing disparity between those who are rich and getting richer, and those who once hoped to become rich but have felt left behind. Directly or indirectly, many of the newest fortunes have been produced by the stock market. Even owners of successful industrial or commercial businesses have been helped by going public and by the subsequent appreciation of the stocks of the companies they own or control.

At the same time, a smaller group became even richer. I used to count myself among the 1% of richest Americans, but recently, the ranks of the 0.1% of richest Americans have ballooned. The beneficiaries have been the creators of “disruptive” companies, but also their investment bankers, advisers, and hedge fund managers, who often receive stock-linked compensation that may be occasional but stands to create immediate, large fortunes. What’s more, while they still represent a minority, they have become an increasingly visible one.

Basically, I now feel like part of the very comfortable middle class. But this is not necessarily how others perceive me.

The 1% who have passively participated in this enrichment include my clients and myself; a consequence of the automatic appreciation of the assets we own. Although we now belong to a second class of the rich (behind the 0.1%), to the rest of the world and to some politicians, we are a class that deserves to be punished by the reversal of political momentum toward the “working” classes, in my opinion.

How do we protect ourselves as investors?

One way or another, and whether or not policies achieve campaign promises, the motto is likely to become “tax the rich.” We’re likely to see increased taxes on the highest incomes, wealth taxes, taxation of the carried interest on private equity, etc. I believe escaping such financial obligations will become increasingly difficult, if not outright risky.

On the other hand, I am convinced that the best way to invest remains to own shares of successful businesses and that the most logical way to participate in this wealth creation is the stock market. I believe the best way to protect ourselves is to avoid investing in tax-oriented deals (which may be withdrawn) and to avoid dependence on businesses that reflect incentives granted by more socialistic government policies.

The universe of companies that avoid these pitfalls — both in the United States and abroad — is substantial and has become even larger after the recent corrections. I believe that it is no time to abandon the stock markets. However, we must work harder in our selection of investments and tighten our selection criteria to adapt them to the changing political environment.

François Sicart – February 14, 2023

Disclosure:

The information provided in this article represents the opinions of Sicart Associates, LLC (“Sicart”) and is expressed as of the date hereof and is subject to change. Sicart assumes no obligation to update or otherwise revise our opinions or this article. The observations and views expressed herein may be changed by Sicart at any time without notice.

This article is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.