Beyond The Headlines

Beware of Economic Forecasts in Investing

A Sequel to “Always the Wrong Question”

www.sicartassociates.com/always-the-wrong-question

As a group, economists (or practitioners of what is often called “the dismal science”) have failed to anticipate some of the most severe recessions and best economic recoveries of the last century. Even as a professed contrarian, however, I cannot defend their forecasting record. I would also take with a grain of salt the advice of investment strategists who base their recommendations on what economists expect the economy to do. Paraphrasing Goethe, “when ideas fail, [big] words come in very handy.”

The Economy and the Stock Market Are Two Different Animals

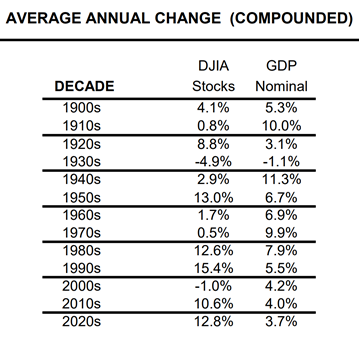

Crestmont Research (www.crestmontresearch.com) produces a wealth of stock market and economic data primarily focused on medium and long-term cycles, which I have often used in these letters. Their latest update contains a table that shows the lack of correlation between America’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and its stock market over the years: the stock market appears to move independently from the growth of the economy as measured by the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Stock Market P/E Ratios and Interest Rates Tend to Move in Opposite Directions

Another document, from BigTrends.com, illustrates how bond interest rates tend to have an inverse relationship with the Price/Earnings ratio of the stock market, which is the main determinant of short- and medium-term moves in stock prices. Both are generally influenced by the rate of inflation, as the returns on both the stock and bond markets must rise when higher prices erode the purchasing power of money.

This is particularly relevant to today’s environment: on many days, we have seen the stock market rise because some strong economic statistics were released. But, as we write, interest rates still stand near historic lows. It appears that the investment crowd has been ignoring the fact that a faster-growing economy might strengthen the resolve of the Federal Reserve to let interest rates rise to more natural (less manipulated) levels and that higher rates tend to depress stock prices through a downward adjustment in the Price/Earnings ratios of shares. If the economy further strengthens, and unless corporate profits actually go through the roof, a stronger economy might not actually be good news for the stock market. So, we have to ask ourselves: “Could corporate profits go through the roof?”

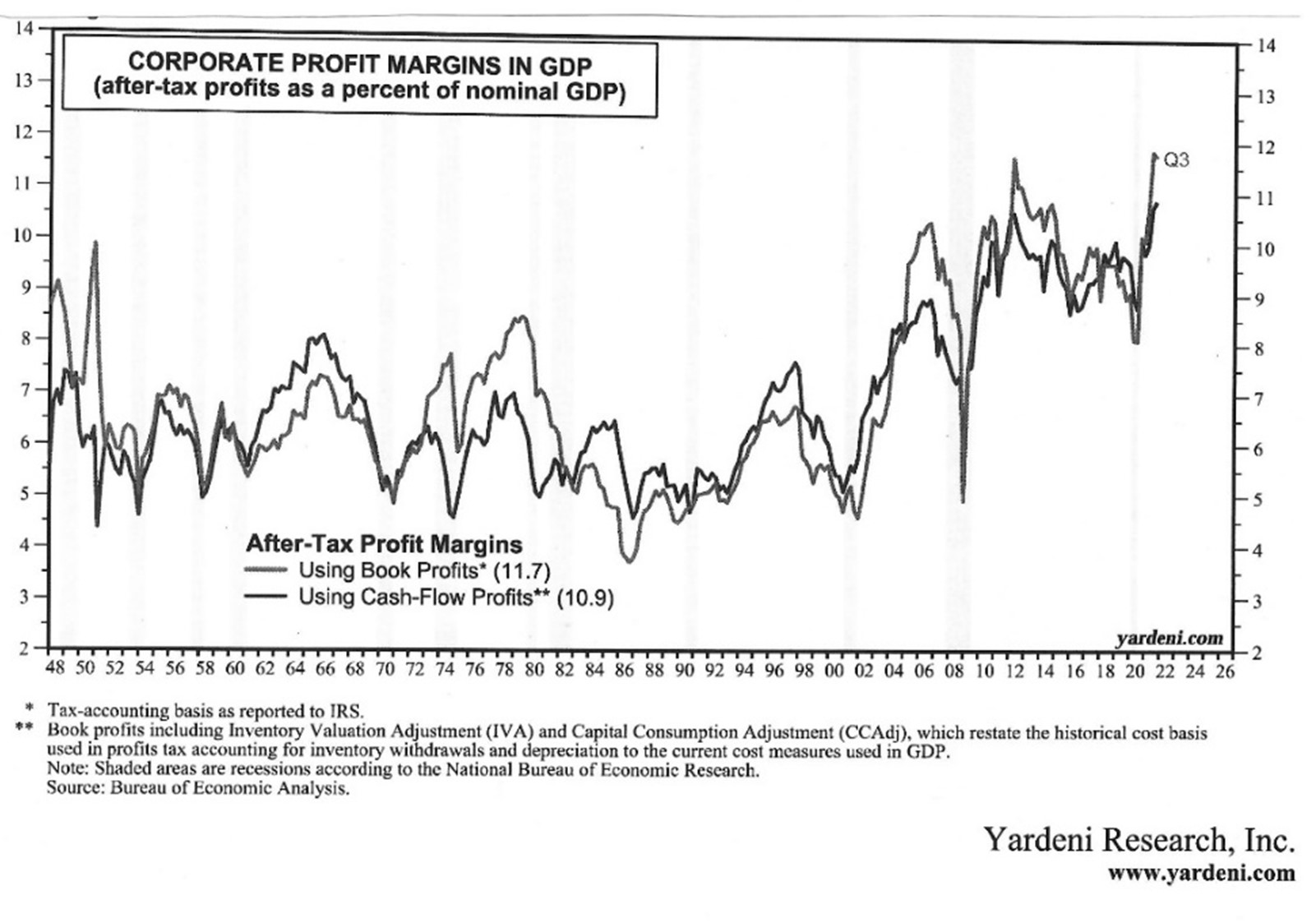

Profit Margins Are Already at a Record

The chart below, from another source of very valuable statistics – Yardeni Research, Inc. — clearly shows that, after moving in a fairly stable range until the early 2000s, corporate profit margins have shot up in the last several years.

Several factors seem to have contributed to this increase in reported profitability.

First, the composition of the American GDP has changed, with lighter industries growing faster and making up a larger share of the pie. Because they use less materials and sometimes direct labor, they tend to have higher gross margins and more relatively-fixed overhead. This gives them greater operating leverage – profits tend to grow faster than revenues when sales increase.

Second, during the uncertain times that we have confronted in the last several years, corporations have naturally tended to underinvest, especially in projects with long-term horizons. This reduces depreciation, which comes as an annual charge against reported income, thus boosting reported profitability.

Additionally, while the purchases do not necessarily show up in aggregate, economy-wide sums like the GDP, corporations have been buying back large numbers of their shares in the open market.

“All told, buybacks may exceed $870 billion for 2021, according to Silverblatt’s data. That would eclipse the record of $806 billion from three years earlier when companies used repatriated funds from the federal tax overhaul.” (Bloomberg)

Buybacks reduce a corporation’s number of outstanding shares and, as a result, increase its reported earnings per share. This will be reflected directly in the performance of capitalization-weighted indexes such as the S&P 500, especially since some of the largest-capitalization companies, which have not reinvested all their cash flows in their businesses, have been the most active in buying back their shares. The buybacks create a disproportionate effect on the behavior of major indices, prompting the stock market to perform better than the GDP in recent quarters.

Finally, even the real economy has benefitted from the pandemic in a somewhat perverse way. Liquidity injections from the Federal Reserve have enriched the wealthier, stock-owning segment of the population, while income-supporting budgetary assistance has helped poorer households and small businesses. Since opportunities to spend that extra money were limited by the pandemic, overall savings have built up, which are being released into the purchase of goods and services now that these restrictions are being loosened.

The Paradox of Inflation

William E. Simon, Secretary of the Treasury during the Nixon administration, once remarked that the American people have a love-hate relationship with inflation. They hate inflation but love everything that causes it. We have enjoyed what causes inflation (more liquidity, government spending, and an ebullient stock market) for the last several years and must now face the consequences of the phenomenon itself. If history is any guide, those results will come in the form of diminished spending power and higher interest rates that will depress stock market and real estate valuations.

A De-globalizing World

No one knows how the Russia-Ukraine situation will evolve, but its sequels will most probably affect the global economy for an extended period of time. We believe that supply chains will be disrupted for longer, and some may be permanently shut off; financial flows will be redirected and become less fluid and more expensive; several commodities, including agricultural ones, will remain more expensive.

Geopolitically, one of the main goals of Russia’s original saber-rattling and natural gas blackmail to Europe was to disrupt NATO’s unity, which is why I had assumed that an all-out invasion might be unnecessary.

For the moment, the way things have been going, Mr. Putin’s war seems to have actually reinforced NATO’s solidarity. But when the immediate fears abate, I suspect that the internal tensions of many global organizations – including NATO, the United Nations, and the European Union — will resurface. In sum, the globalization of the world economy, which was one of the motors of post-WWII economic prosperity, may recede or need to be re-invented.

* * *

I have often referred in these pages to Hyman P. Minsky, a professor of economics at Washington University in St. Louis and a distinguished scholar at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, who introduced The Financial Instability Hypothesis in 1992.

This hypothesis essentially posits that stability is destabilizing. If the economy or financial markets remain stable (for example, within a well-established uptrend) for an extended period of time, the attitudes of economic and financial participants change as they become more willing to accept risk (debt) and speculation.

To me, the most important implication of the hypothesis is that economic recessions or financial crises do not need an immediate trigger to happen: they are due to the very nature of free markets and crowd psychology. What has been labeled a Minsky Moment refers to the onset of a market collapse brought on by the reckless speculative activity that defines an unsustainable bullish period. It cannot be precisely predicted, but one can prepare for it.

Today, as inflationary pressures linger, especially on the cost side, recessionary forces may also become more prominent. As usual, good investors should remain alert and prepare for both.

Good luck and clear minds…

François Sicart – March 7th, 2022

Disclosure:

The information provided in this article represents the opinions of Sicart Associates, LLC (“Sicart”) and is expressed as of the date hereof and is subject to change. Sicart assumes no obligation to update or otherwise revise our opinions or this article. The observations and views expressed herein may be changed by Sicart at any time without notice.

This article is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.