Beyond The Headlines

Buying companies when they lose money

One of my early and most influential mentors, Walter Mewing, began his career before the Great Depression as a messenger on Wall Street. Reportedly, just before the onset of the Depression, he sold all the stockholdings he had managed to accumulate from his small savings in order to buy a chicken farm. Upon returning to Wall Street in the early 1930s, he embarked on a career as a financial analyst and investor. Somehow, he became a partner with my other two (much wealthier) mentors and the much younger Christian Humann, who eventually became my boss and, ultimately, partner.

Walter Mewing had one passion in life: financial analysis. He was devoted to the philosophy of Benjamin Graham, the Columbia University professor who is widely considered the father of value investing. But Walter was no academic. I believe he was self-taught, and had acquired his knowledge in the field and by reading endless annual reports (including the SEC-mandated footnotes to the financial statements). By the time I knew him, he assiduously attended the daily meetings of the National Association of Security Analysts, where listed companies would make presentations and answer questions. Even his vacations were usually spent visiting companies.

On a few occasions, as we were discussing companies going public out of venture-capital firms, he had advised me, “When a company has no earnings yet, there is no upper limit to its share price, because it is selling on the basis of dreams. But be careful when it starts making money, because it will then begin selling on the basis of hard figures from its income statement and balance sheet, and its price is likely to fall back to earth.”

Today, with the recent years’ popularity of “unicorns” (billion-dollar start-ups), many of which are still not earning any meaningful profits, there is a plethora of shares to avoid if an investor wishes to follow Walter’s advice.

On the other hand, I remember that in the late 1990s, when the dot.com boom was raging, the price of many industrial metals had collapsed and many mining companies were losing money. My then-partner John Hathaway asked for a meeting of the senior members of the firm to make his case for what a mining company like Phelps Dodge could earn if only the price of copper returned to the level it had reached several times in previous years. I don’t have a detailed recollection of the episode, and no longer have access to Phelps Dodge trading at that time. But — based purely on memory — John’s case was very convincing to me because I had witnessed this kind of cycle on a few occasions.

When business is good and the price of copper is high, all producers tend to open new mines at the same time, eventually resulting in overcapacity and low prices. Subsequently a few financially-marginal producers might close, while stronger ones simply cut capital spending. As a result, the supply/demand balance is restored. Then a new investment boom will generally get underway, but it takes several years to build new mines and reopen operations, so that copper becomes scarcer and thus more expensive.

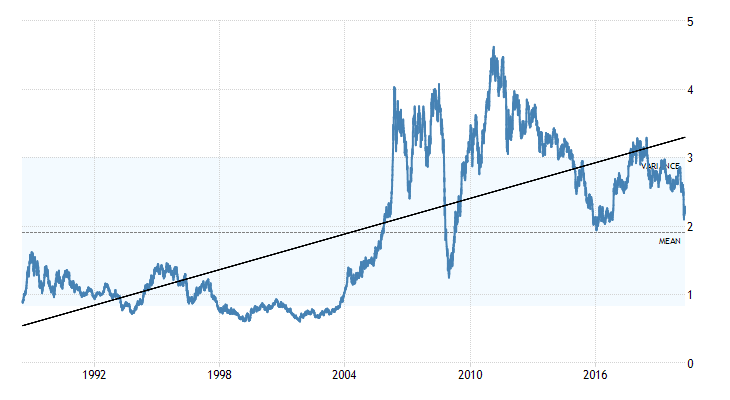

The following chart will give an idea of the situation at the time. I believe the price of copper had collapsed to around 65 cents per pound and stayed in that range for a while. But by the early 2000s it doubled to levels it had previously reached in the late 1980s and mid-1990s. (As can be seen from the chart below, it then went on to attain much higher prices, but that is another story and by then our firm had probably sold out of our copper investments.)

Copper Price $/lb.

The lesson I retain from that episode is that cycles in industrial commodities prices take time to unfold. Yet because producers tend to behave as a crowd, investing and cutting back at roughly the same time, lagging behind the physical supply/demand dynamics, these companies also tend to oscillate between rich profits and deep losses. Of course, this is my opinion and history does not always repeat itself. But it tends to “rhyme”.

So, how does this apply to the current situation?

The Coronavirus pandemic and its dramatic effect on the world economies pretty much guarantee that some economic sectors will be losing money for at least a couple of quarters and possibly longer. My observation, over the years, is that most financial analysts and the investors who follow their advice do not look much further than a few quarters in advance, if that much. This is especially true when corporations themselves stop issuing projections, as is now the case. Thus, we believe it is likely that the shares of companies in the sectors most affected by the developing economic vacuum — such as hotels, restaurants, airlines, shipping, and many companies involved in tourism or international trade — will sell as if they would never recover.

Of course, some companies will go out of business in the industries most directly affected. Nevertheless, the financially stronger ones will probably survive to enjoy the next boom in demand for a diminished supply of their products or services. As often in periods like this, it will be important for investors to select, not companies that felt comfortable and aggressive when liquidity was plentiful and readily accessible, but those that have low debt, ample reserves of cash, and the ability to survive several quarters of negative cashflow without curtailing essential operations.

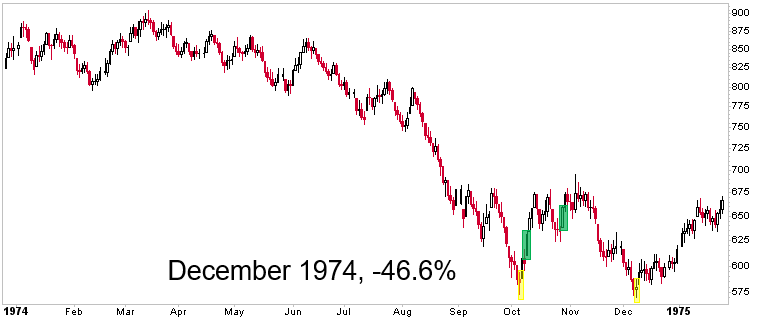

One last memory flash: the 1973-74 bear market erased almost 50% of the Dow Jones Industrials value in almost two years before it was concluded by a double (or W-shaped) bottom in the three months between October and December 1974. In view of the rapidity and violence of both the decline and recent bounce in 2020, a similar pattern would not be overly surprising. Please also note that the 1974 economic recession only ended officially in March 1975.

Dow Jones Industrial Average from January 1974 to February 1975

Source: A History of Stock Market Bottoms – TheIrrelevantInvestor.com — Dec 27, 2018

* * *

Just as those patients with otherwise good physical health will likely survive the Coronavirus pandemic and recover from intensive care to prosper and possibly help other patients thanks to a newly-acquired immunity, the financially-stronger and more resilient companies will likely be the survivors from the economic recession and contribute to the future recovery of the country’s whole economy.

François Sicart – April 15, 2020

Disclosure:

The information provided in this article represents the opinions of Sicart Associates, LLC (“Sicart”) and is expressed as of the date hereof and is subject to change. Sicart assumes no obligation to update or otherwise revise our opinions or this article. The observations and views expressed herein may be changed by Sicart at any time without notice.

This article is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.