Beyond The Headlines

Liquidity vs. Reality

As I began writing this paper, the following headline flashed on CNBC.com: Wall Street rally gains steam, with the Dow up 900 points after record surge in US jobs. It didn’t take long for the media to endorse a new narrative: Trump declares jobs coming back on heels of surprise labor report (FoxNews.com) and Trump: This is a ‘rocket ship’ recovery (Yahoo.com), for example.

To me, these are just the latest instances of how, in the last few years, financial markets have been interpreting any kind of good news, or even the simple promise of good news, as a signal to jump onto the bandwagon of the decade-old bull market and, in today’s language, to adopt a risk-on investment posture.

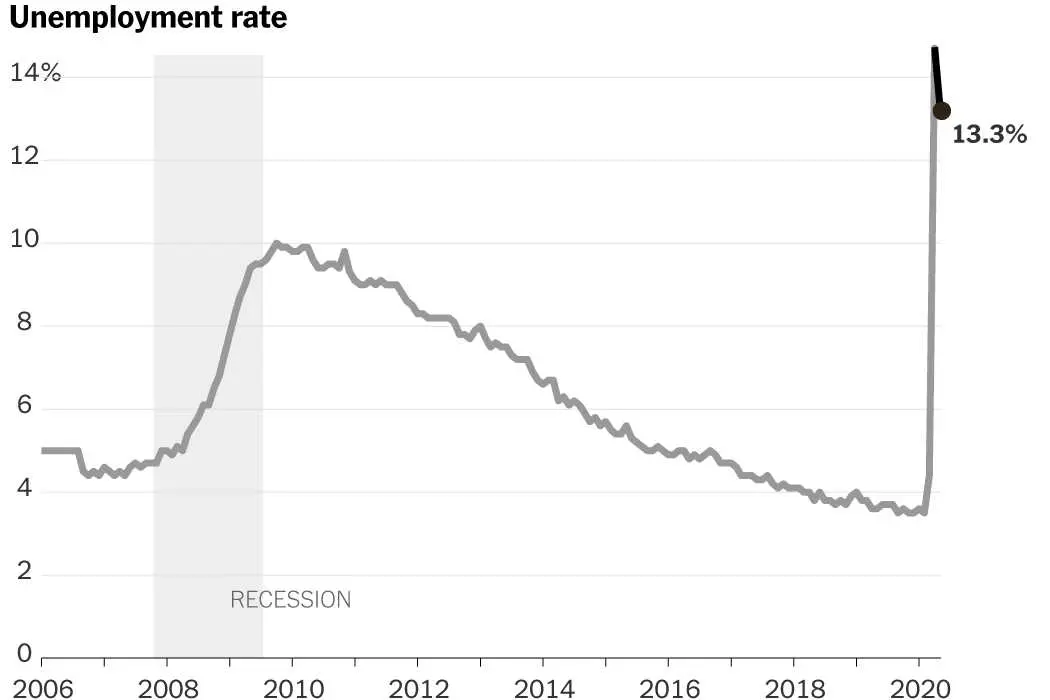

As these headlines popped up, 30 million workers were still collecting unemployment benefits in the real world. In an interview with the Washington Post Jay Shambaugh, an economist at the Brookings Institution, pointed out that “… a 13.3 percent unemployment rate is higher than any point in the Great Recession. It represents massive joblessness and economic pain. You need a lot of months of gains around this level to get back to the kind of jobs totals we used to have.”

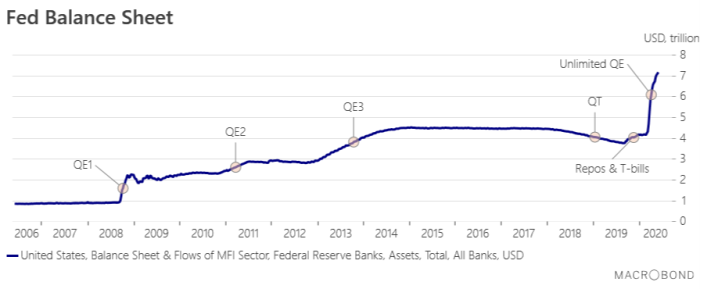

A combined look at the two charts below makes it clear that the recent stock market bounce is disproportionate to the small downtick in unemployment.

In their May 15, 2020 Market Perspective, Charles Schwab strategists recall that “Some investors were surprised by US stock market gains in April and early May, during a period of dismal economic news. Although the US unemployment rate surged to 14.7% in April, a month in which 20.5 million jobs were lost, the S&P 500© index rose 13%.” Yet, as we know, the bad news continued into late May and early June, and on Jun 6, 2020 The Journal Times of Racine, Wisconsin recollected:

“On March 23, 3.3 million people had newly filed for unemployment under lockdown efforts. At the time, 31,000 Americans had been diagnosed with COVID-19, and about 400 had died. On that date, the S&P 500 hit bottom, down about 34% from the high on Feb. 20 …Fast-forward to today, and there are almost 1.8 million confirmed COVID-19 cases, more than 114,000 Americans have died, and millions more people are out of jobs as unemployment has skyrocketed to almost 15%. Yet the market is 37% higher than it was 10 weeks ago.”

On top of this, in the last two weeks, millions of protestors – mostly peaceful but sometimes violent – have confronted the police and the National Guard, barely avoiding a controversial call for the military to intervene to “dominate” the civilian insurrection.

As a contrarian, I subscribe to the old adage: “Buy when there’s blood in the streets.” However, I usually find it safer to be a contrarian on financial markets than on fundamental economics or politics. And, given the recent behavior of the financial markets, it is more tempting for me as a contrarian to be cautious than to join the crowd of investors afraid of missing out.

In their paper mentioned earlier, the Schwab strategists explain:

“… one of the more powerful forces driving markets has been the massive injection of liquidity from both the Federal Reserve and Congress. The Fed’s balance sheet has grown exponentially, surpassing $6.7 trillion as of May 6, as the central bank bought securities in an effort to support prices and flood markets with cash [See chart below]. Meanwhile, Congress has reacted to the COVID-19 pandemic by doling out more than $2.5 trillion … to taxpayers and businesses in the form of direct relief payments, loans and grants.” They conclude that section as follows:

“At the March lows, stocks were pricing in the kind of economic collapse we’re currently in the midst of. However, the subsequent rally was less about economic optimism, and more about Fed-provided liquidity.”

Recent Bloomberg.com articles (June 3 and 9, 2020) pointed out that much of the most recent stock buying came from (small) brokerage customers. Trading activity among individuals has almost tripled this year, according to data from retail brokerages compiled by Goldman Sachs.

Apparently, retail investors’ buying power has replaced the share buy-backs of corporations, which reportedly were a main factor behind the 2018-2019 stock market advance but have since subsided.

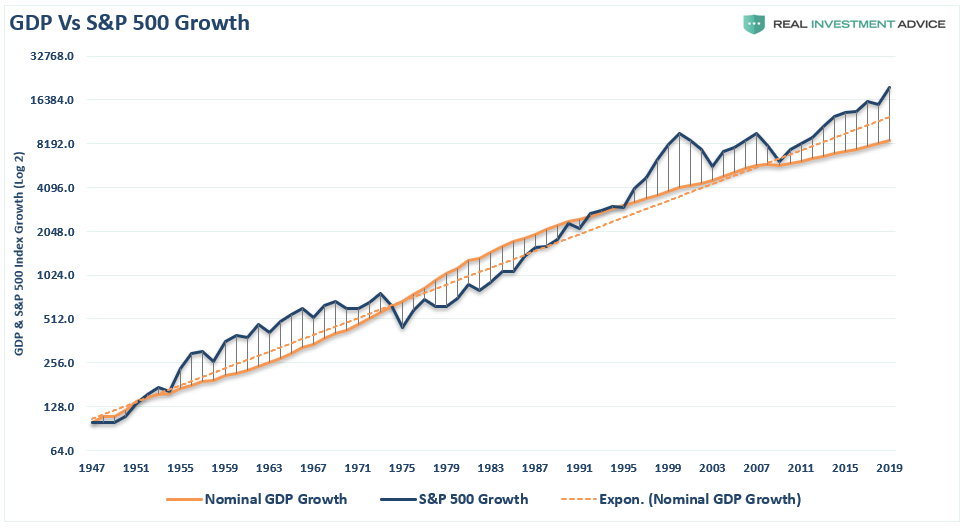

I have long been convinced that there was at best a loose relationship between economic activity and the stock market. Certainly, the financial markets are much more volatile over short or medium-term periods, and the dichotomy between the two can persist for many years.

I am fully aware that, historically, the stock market tends to turn up or down ahead of the economic cycle. But it seems to me that from a cyclical point of view, the market has discounted by a wide margin any significant recovery from the COVID-associated recession.

In his June 5 “On My Radar” newsletter, Steve Blumenthal mentions that the S&P 500 median P/E ratio now sits at 24.6 times trailing 12-months earnings vs. a 52-year average of 17.3 times. Now that the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ 100 have approached or exceeded the levels reached at the February 2020 stock market peak, the real questions are whether the economic recovery will be as fast as the market seems to have anticipated, and whether some unanticipated developments might still rock share prices.

It is wise to remember that price/earnings and other valuation ratios are not very useful as predictors of the stock market over the short-term but can give a very good idea of future returns over a 7-10-year horizon. (See Crestmont Research et al.)

As for the speed of the recovery, I am willing to accept the scenario of a sharp bounce from the bottom of the recession, when a significant share of the economy was shut-in. But I find it hard to imagine the previous peak in economic activity being equaled or exceeded while many labor-intensive businesses (travel, hotels, restaurants, and possibly shopping malls and office space rental) will not fully recover or fully re-hire their past personnel any time soon.

In terms of unanticipated developments, they are by definition hard to forecast, but they might occur in weak parts of the economy. For example, the May 16, 2020 issue of The Economist foresees “a wave of bankruptcies” ahead, and Steve Blumenthal cites James Bullard, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, warning that: “You will get business failures on a grand scale” (May 12, 2020). Edward Altman, Professor Emeritus at NYU’s Stern School of Business and inventor of the Z-score for predicting bankruptcy, also expects at least 165 large firms with more than $100 million in liabilities to go bankrupt by the end of 2020.

The more I watch the rapidity of daily developments in the economies and the financial markets, the more I am tempted to prepare for a continuation of a W-shaped behavior for the US stock market in coming months. As we observe the appearance of economic green shoots in late 2020 and early 2021, it will be prudent to watch for any over-discounting of the economic recovery by the financial markets.

François Sicart

June 12, 2020

Disclosure:

The information provided in this article represents the opinions of Sicart Associates, LLC (“Sicart”) and is expressed as of the date hereof and is subject to change. Sicart assumes no obligation to update or otherwise revise our opinions or this article. The observations and views expressed herein may be changed by Sicart at any time without notice.

This article is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.