Beyond The Headlines

Preparing to be prepared

I began my investing career in 1969, following the value philosophy enunciated by Benjamin Graham in his seminal book Security Analysis (1934) and the later (and lighter) The Intelligent Investor (1949).

One of the earliest and simplest approaches advocated by Ben Graham was to buy shares of companies selling at or below their net working capital, which he calculated as adjusted current assets minus total liabilities. “Adjusted current assets” included cash and cash equivalents at full value, accounts receivable reduced for doubtful accounts, and inventories at liquidation values. Graham’s reasoning was that, following that formula, you would buy a company at or below its strict liquidating value and would receive for free all its other assets (land, buildings, equipment, etc.).

That original approach was therefore derived almost entirely from the companies’ balance sheets. Less weight was given to profits and even then only actual, realized earnings were included, rather than estimated or projected ones.

From Value to Contrarian Investing

In those ancient times – before 1981 — there were no personal computers. The machines then available were bulky, expensive, slow, and lacked today’s omnipresent and user-friendly software. Similarly, large financial databases were mostly distributed in printed format (like the traditional phone book!) or for use only on very powerful computers; generally, they were not accessible to small users. If you were able to consult the few existing databases and had the patience to search them for the stocks offering the kind of value I define above, you were one of a relatively small number of professionals and life was good for value investors.

Unfortunately, in subsequent years, technology ruined the idyllic advantage enjoyed by early value investors.

First, the introduction of cheap and very fast personal computers, the digitalization of large financial databases and the development of filtering tools put the calculation and sorting of simple ratios such as Graham’s “share price to net working capital” within the reach of even unsophisticated investors and run-of-the-mill financial journalists.

Second, as industry became lighter and supply chains more global, we were still using 19th-century accounting to assess the businesses of the 20th and 21st centuries: traditional accounting, invented when raw materials and manual labor constituted the bulk of business costs, ceased displaying an accurate picture of modern companies’ results and financial strength. In particular, asset-light companies in electronics, service industries, and eventually those involved in or using the Internet had fewer hard assets on their balance sheets. Furthermore, the values of the assets they reported (such as patents, know-how, contracts and other so-called intangibles) were difficult to appraise. Even profit and cash-flow figures increasingly became subject to management choices and interpretations.

Thirdly, in an era like the present when many industries are new or are disrupted by new entities with novel business models, it has become difficult to assess “value” Perhaps as a result, corporate managements have begun to promote criteria other than the traditional profitability to analyze the performance of their companies. Not surprisingly, the financial media and many financial analysts have begun to focus their reporting on these new yardsticks, which now often overshadow more tangible results.

When I started in the investment business, the terms “value” and “contrarian” were practically synonymous: If the shares of a company sold at a low price compared to their calculated value, it indicated that this company was not in great favor with investors and thus presumably cheap. Over time, one could hope to make a significant profit at a relatively low risk if and when the market brought prices more in line with intrinsic values, or sometimes above them. As the notion of value was slowly being eroded by the changes described above, I have found it useful to emphasize the contrarian aspect of my investment discipline, while keeping measures of value as checking tools to preserve the rationality of my stated contrarian/value approach.

The Rise of Contrarianism

In recent years, behavioral finance has taken center stage in the analysis of human strengths and weaknesses in investing, in particular thanks to the awarding of Nobel Prizes to two leading practitioners of the discipline: Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler. One of the interesting distinctions that has arisen as a result of all this work is the one between momentum investing and contrarian investing.

Momentum investing consists of buying securities that have had high returns in the recent past, on the assumption that superior price performance tends to continue… for a while.

Contrarian investing consists of purchasing and selling contrary to the prevailing sentiment of the time. The assumption is that crowd behavior among investors generates excesses of optimism and pessimism that create exploitable episodes of mispricing in securities markets.

The paradox I have observed over the years is that momentum investors are right most of the time – especially in rising markets — as what has gone up will usually continue to go up for a while. Since it is difficult to recognize when excesses have become unsustainable, momentum investors can make steady albeit relatively small gains during bull markets. However, since trees don’t grow to the sky, they usually miss the major turning points in a costly way. In contrast contrarian investors usually forego the speculative phases of rising markets, but can realize big gains when it counts, i.e. when bubbles burst and in their aftermath.

A Major Turning Point?

The Coronavirus pandemic and its increasingly predictable economic consequences are likely to trigger a change of tone in the markets after the economic recovery from the 2008-2009 “Great Recession”, in which the decade-long spectacular performance of the stock and bond markets has been recently interrupted by trading volatility. This may foreshadow the imminence of a major turning point in financial markets.

Given the difficulty of evaluating the future in the midst of the current crisis, the question we ask ourselves is how to be a successful contrarian investor today. Without going into the details of specific industries and companies, we discern several macro trends that are likely to affect all major sectors of the economy if and when they reverse.

Interest Rates as a Contrarian’s First Choice

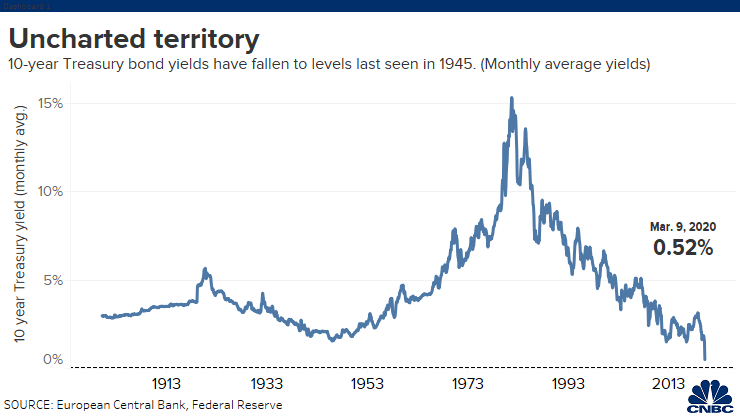

After a peak at more than 15% in 1981, the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds has been in a relentless decline to almost zero at this writing. This means that bond prices have been in an unprecedented bull market for 38 years.

Declining and very low interest rate, in my observation, tend to make things look easy. Some beneficiaries simply take it for granted, while some speculators and would-be entrepreneurs optimistically credit their early successes to their business acumen and view it as an encouragement to take more risk.

As a rule, we at Sicart do not sell short, though we have very occasionally used “inverse” Exchange-Traded Funds (ETF) that move in the opposite direction to their underlying securities. Nevertheless, it is tempting to look for investments that would benefit from a recovery or “normalization” of interest rates.

I should remind readers that the argument for interest rates bottoming out could have been made at almost any time in the last few years – and it was, including by me. Now, many other economies have engineered negative interest rates, where lenders actually pay you to borrow money! Perhaps more importantly, some credible economists, including Harvard professor and former IMF director of research Kenneth Rogoff, have argued “The Case for Deeply Negative Interest Rates.”

With central banks desperate for new monetary tools, the suggestion may seem attractive, although it is not clear that countries which have adopted that approach (including Japan, Switzerland, and several European Union members) have benefited a great deal. One of the risks of “deeply” negative interest rates is that they would be an incentive for populations to save rather than spend, with obvious recessionary or deflationary implications — at a time when global governments are trying to engineer an acceleration of their economies.

Deflation or Hyperinflation?

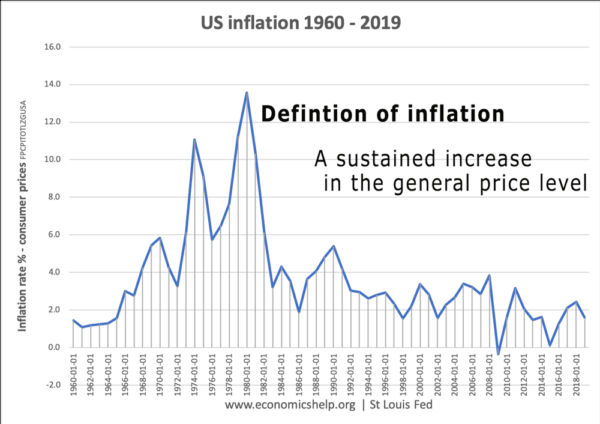

Readers will not be surprised to see on the graph below that the U.S. inflation rate has followed more or less the same pattern as interest rates (shown earlier). When inflation rises and erodes the purchasing power of money as a result, interest rates must also rise to compensate savers.

My experience with high inflation is rooted in the 1970s, and when I see huge government spending programs and gaping budget deficits, I am reminded of President Lyndon Johnson’s “Guns and Butter” policies during the Vietnam war years, which ushered in the inflationary bubble of the early 1970s. Indeed, it is hard for me to envision how today’s massive income-maintenance policies and the further programs to stimulate the world economies could not, in time, cause a re-acceleration of inflationary pressures.

On the other hand, a number of prestigious economists foresee a continued period of slow growth, over-supply of both goods and labor, and overall dis-inflation if not deflation (declining prices). In particular, Lacy Hunt of Hoisington Investment Management Company and Harvard University’s Kenneth Rogoff point out that rescuing already-overindebted governments by issuing more debt causes a decline in the stimulative power of the new debt and a slowdown in the growth trend of the borrowing countries. Accordingly, some economists anticipate years of dismal growth ahead for the United States and other leading economies.

At this juncture, I find it hard to discern whether inflation will prevail as a result of the massive sums thrown at the world’s economies or if, on the contrary, weak demand and oversupply of goods and services will send the global economy into a decelerating spiral accompanied by debt defaults and declining prices. For someone who, like us, prefers to “be prepared” rather than make predictions, both scenarios are credible and can be envisioned, possibly within different time frames.

Is Gold an All-Terrain Vehicle?

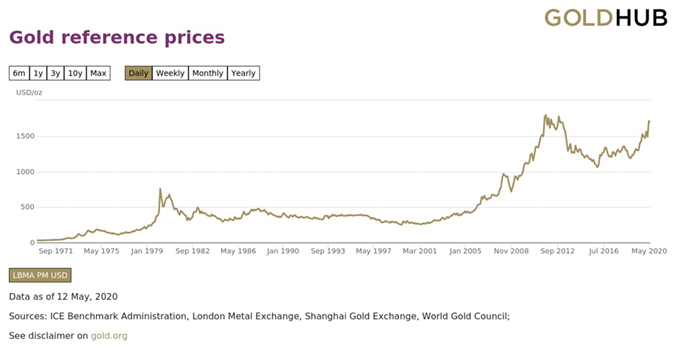

Before I joined him at Tucker Anthony, my mentor and later partner, Christian Humann had already established investment positions in gold mining shares, when gold was trading in the low $40s per ounce, if I remember well. In my early years as an analyst, inflation was accelerating and the portfolios under our supervision benefited accordingly. This lasted for a number of years, but Christian often asserted that gold offers protection in inflationary periods but would do the same under deflation.

Since, at the time, I was primarily concerned about inflation, I did not pay too much attention to the deflationary argument, even though in the late 1970s I authored a report somewhat pompously entitled “Between Inflation and Deflation – The Dislocating World Economy.” The principal benefit from that report was that one day I received a letter from René Larre, then the General Manager of the Bank for International Settlements, congratulating me on my analysis and pointing out that he had made similar arguments in a recent speech. That was the beginning of a stimulating relationship that lasted several years until his retirement.

We usually met for lunch once a year at a restaurant close to the BIS tower in Basel (Switzerland). Because of his participation in regular meetings of the world’s leading central bankers, Mr. Larre was very careful never to share with me anything sensitive. Similarly, by courtesy, I avoided any questions dealing with his classified activities. We just chatted about economics and the general state of the world.

By the late 1970s, however, the price of gold had risen exponentially to around $800 per ounce and had become the talk of the town in financial circles. I casually asked Mr. Larre what he made of this and he answered just as casually: “Of course, I have no particular information, but gold looks a bit toppy to me.”

Mr. Larre and I were so used to avoiding sensitive topics that I paid no attention to what, in retrospect, could have sounded like a very timely piece of advice. As can be seen from the graph above, it took more than 20 years for gold to resume its 1980 price. I did sell Christian’s very successful investment in gold mines sometime later but my obliviousness to the sagacious opinion of my lunch companion at what turned out to be a major historical top demonstrates my preference (at the time) for theory over trading practicality.

As a result of mulling over these events, I called my former partner John Hathaway, one of today’s foremost experts on gold, to see if he might elucidate Christian Humann’s claim that gold could protect investors in both inflationary and deflationary times. One of the points that stood out for me from a lengthy and learned conversation is that, besides being a hedge against inflation, gold tends to be a refuge against chaos and uncertainty. The kind of deflation that experts like Lacy Hunt and Kenneth Rogoff envision in coming years is likely to be accompanied by many corporate defaults and generally deteriorating balance sheet values. With interest rates at zero or below and the solvency of corporations in doubt, investors will be hard-pressed to invest their savings or their pensions. At that point, gold may once again appear as the ultimate safe haven.

A Contrarian View of Oil

One reason for the strong performance of gold in recent months is that it has benefitted at the same time from a rising price for the commodity itself and flat or declining costs of its two main mining inputs: labor and energy. For different reasons, almost the opposite can be said of petroleum.

Normally, supply and demand for a commodity will trend together, although with significant leads and lags, which cause the main fluctuations in price. This is because increased demand tends to eventually attract higher production, while decreased demand will eventually result in a cut of productive capacity, after shutdown costs and delays.

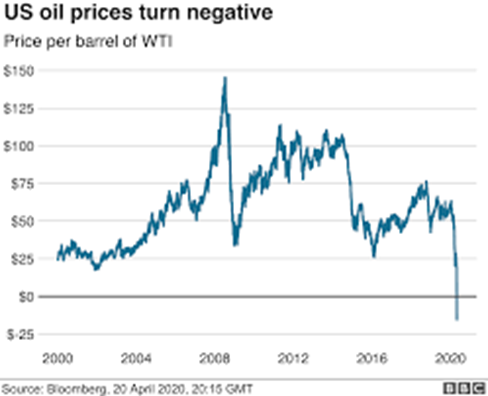

Atypically, in early 2020, a major disagreement caused a price war between the two leading members of the OPEC-Plus oil producing group – Saudi Arabia and Russia. Russia refused to join the production cuts demanded by Saudi Arabia and the kingdom retaliated by massively increasing its own production, pushing down oil prices accordingly. When the Coronavirus pandemic then practically destroyed many sources of demand for oil, the world was simultaneously faced with an artificially-inflated supply, and a depressed demand for petroleum.

When oil is not selling, production continues and the excess oil produced must be stored. In April, we reached a point when all storage space, including empty tankers, had been filled. With the resultant shortage of storage capacity to contain the incoming supply of oil, desperate traders and producers briefly had to accept a negative price to get rid of their production and inventory.

Since then, assisted by OPEC-Plus members’ production cuts and some “re-opening” in the most visible world economies, the price of oil has recovered somewhat to around $33 — but well short of the more than $60 it commanded less than a year ago. Judging by the tone of specialized media, the investor consensus for the longer term still contains a hefty dose of skepticism and pessimism about oil. This is why the views of natural resources experts Goehring & Rozencwajg make an interesting contrarian argument.

Goehring & Rozencwajg estimate that, sometime in May, global oil consumption was oversupplied by 21 million barrels per day. If world storage remains around full capacity, “a good portion of that 21million barrels per day will have to be shut in.” This is significant when compared to global oil consumption of probably around 100 million barrels per day before the trade war and virus crisis, and around 80 million barrels per day in April.

They offer an array of reasons why oil production is set to decline sharply in the next few years, if not sooner. Once global storage is full, the global petroleum supply chain will be forced into a “just-in-time” mode, where supply must equal demand. The recent cuts agreed on by OPEC-Plus are not sufficient to balance global supply and demand, but the recent events will also force producers everywhere to quickly shut in marginal or unprofitable wells. For example:

— Old and small “stripper” wells with declining production and estimated lives

— Expensive heavy-oil production from Canadian oil sands

— Production from offshore locations such as the Gulf of Mexico

— Shale oil production from “fracking”, which has boosted US capacity dramatically in the last couple of years but needs constant investment to prolong the life of its fast-depleting existing reservoirs. (In any case, other studies had previously pointed out that much oil shale production was uneconomical below prices in the mid-40s, which few experts are currently anticipating in the foreseeable future.)

According to Goehring & Rozencwajg, most of the diminished production will never be restored because of the costly investment to revive it or the damage to reservoirs. They also point out that the US oil-rig count has fallen 45% in the last six weeks. Such a decline is not rapidly offset once skilled personnel has been laid off.

To end on a silver lining, the reduction in oil production should also reduce the supply of natural gas, which had not benefited from the bull market in oil. According to a note from Mauldin Economics, 32% of total US natural gas production comes from wells that primarily produce oil. They mention that Goldman Sachs expects natural gas prices to double by the end of the year.

* * * * *

Good luck being prepared!

François Sicart – May, 27 2020

Disclosure:

The information provided in this article represents the opinions of Sicart Associates, LLC (“Sicart”) and is expressed as of the date hereof and is subject to change. Sicart assumes no obligation to update or otherwise revise our opinions or this article. The observations and views expressed herein may be changed by Sicart at any time without notice.

This article is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.