Beyond The Headlines

Second-Order Thoughts

The always-stimulating Farnam Street blog recently discussed the classic example of The Chesterton Fence. In a 1929 book, The Thing, English writer G.K. Chesterton, offered the following advice:

“Do not remove a fence until you know why it was put up in the first place.”

As Chesterton explained, fences don’t just happen. They are built by people who had some reason for thinking they had a purpose. Until we establish that reason, we have no business taking an ax to them. This observation has become one of the pillars of a discipline that has recently become popular in action-oriented thinking circles: second-order (or second-level) thinking.

As it applies to investments, second-order thinking was clearly illustrated by Howard Marks, in his book The Most Important Thing (Columbia Business School Publishing) and his periodic letters to clients of the firm he co-founded, Oaktree Capital Management:

“First-level thinking says: ‘It’s a great company, let’s buy the stock.’ Second-level thinking says: ‘It’s a good company, but everyone thinks it’s a great company, and it’s not. So, the stock is overrated and overpriced; let’s sell.’”

From my point of view, the second-order approach has several attractive features:

- It clearly is different from the usual approach and, by definition, to be better than the majority of investors, you must first behave differently. (See Howard Marks, above)

- It is contrarian, but in a thoughtful way rather than merely as a reflex.

- It forces one to look beyond the immediate future, which is one way in which we at Sicart try to differentiate ourselves from the crowd of analysts.

So, how should we look at today’s situation from a second-order perspective?

Most world economies have struggled to recover even partially from the so-called Great Recession of 2007-2009. Now, the economic consequences of the Coronavirus pandemic almost guarantee that the world economy is about to fall into recession. Forecasts of recovery and future growth are being scaled back accordingly. So, the consensus looks to and prepares for a recession of still unknown length and depth.

However, to offset the fast-deteriorating outlook, most governments are devising (and promising to soon start implementing) stimulus programs of unprecedented sizes. These programs include what central banks can still do with their few yet-unused tools to sustain liquidity in economies and especially financial markets. But they also incorporate large fiscal spending to sustain jobs and incomes, as well as unprecedented programs to protect or boost activity in industries threatened by the pandemic.

Unfortunately, if there is one thing that history has taught us, it is that it is easier to throw money at a deteriorating economy than to “take away the punch bowl just as the party gets going,” as the late Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin famously advocated. There is a good chance, therefore, that pandemic-relief and stimulus programs will continue well after the health of populations and economies have turned around and started to recover.

To summarize, a first-order look at the current situation tells us that we are taking the measures required to fight a developing global recession. A second-order look tells us that these measures will likely outlast the recession, eventually turn out to threaten budget balances, and possibly trigger a revival of inflationary pressures.

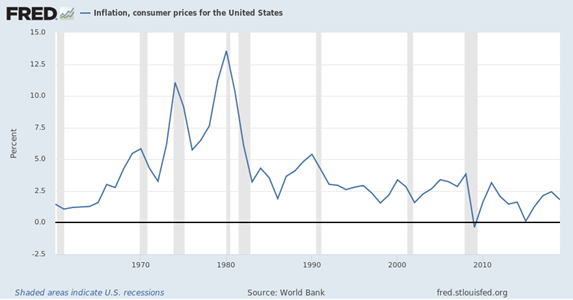

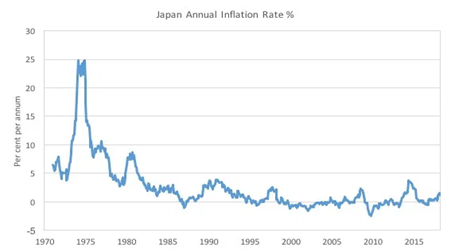

Today, inflationary pressures are very far from the minds of younger observers. The last peak in U.S. inflation was almost 40 years ago and we have since experienced declining and then stubbornly-low inflation, so that younger analysts and investors may have read about it in history books but they don’t remember personally experiencing it.

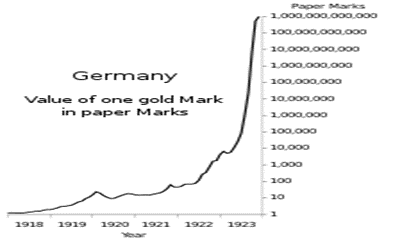

Most current observers are more likely to draw parallels with Japan’s contemporary struggle against deflation than with Germany’s hyperinflation under the Weimar republic, between the two world wars.

My First Encounter with Inflation in the Midst of a Recession

Between January 11, 1973 and December 6, 1974, the Dow Jones Industrial Average lost over 45%. The crash came after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system over the previous two years, then the US dollar devaluation, the Watergate political crisis, and the first oil crisis in October 1973.

As I was trying to remember this first experience of my career with inflation rising in the midst of a global recession, I came across a paper on “The 1972-75 Commodity Boom” which confirmed that paradoxical occurrence (Brookings Papers on Economic Activity Vol. 1975, No. 3, 1975 – Richard N. Cooper, Robert Z. Lawrence).

Thanks to the foresight of my mentor and boss at the time, the late Christian Humann, our portfolios had been holding large positions in shares of raw materials and energy producers. They continued to rise as the overall market decline got under way, significantly helping our performance that year.

In their paper, Professors Cooper and Lawrence summarized: “An extraordinary increase in commodity prices occurred in 1973-74. Even leaving aside crude oil as a special case, primary commodity prices on one index more than doubled between mid-1972 and mid-1974, while the prices of some individual commodities, such as sugar and urea (nitrogenous fertilizer), rose more than five times.” They added that the sharp rise in commodity prices had startled most observers, as it came on the heels of apparent oversupply in 1970-71.

The mechanics of the cycle in industrial commodities need to be kept in mind. Capacity closures are not easy or cheap to implement and are thus often delayed. But once they have been made, it usually takes several years to plan, build, and ramp up new capacity. So, the workings of supply and demand are not well synchronized and can be slow to develop.

The Intriguing Case of Oil

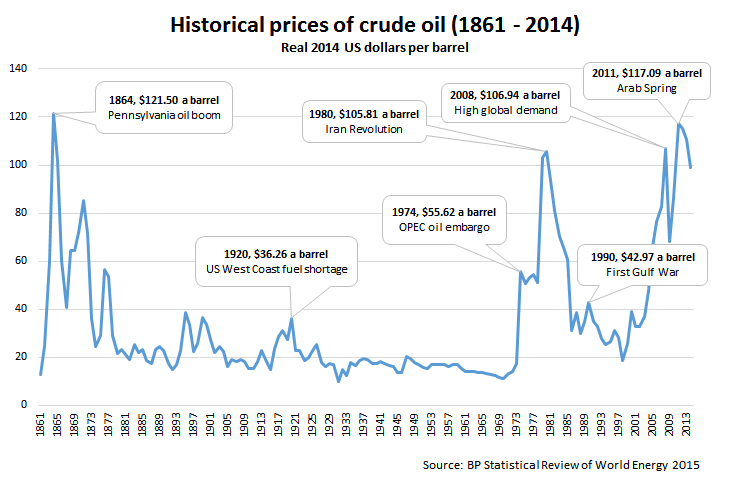

Even though oil was excluded from the 1975 Brookings study because of the volatility caused by the oil embargo and the creation of OPEC in 1973, it has proven to be an excellent case study of such cycles.

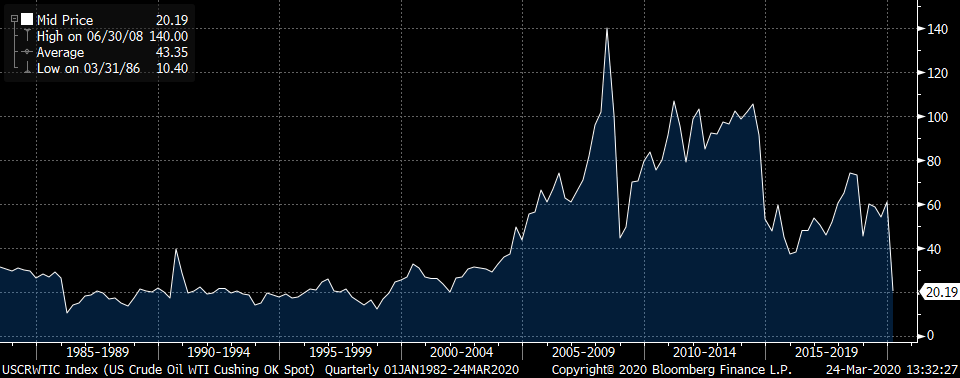

The two charts below are of particular interest.

The first one illustrates that, after the investment boom that followed the second oil shock, triggered by the 1979 Iranian revolution, oil prices began a 20-year, 60 percent decline, except for a brief rebound during the Gulf War.

The second shows that the oil price is now back to its 1990s level of around $20 per barrel.

Of course, there is little doubt that there is a long-term tendency for the world to move from fossil fuels such as oil, gas and coal to alternate sources of energy such as solar, wind, etc. But in a medium-term perspective, for cost/price and infrastructure factors, as well as regional and economic development considerations, this transition is likely to remain relatively marginal for a number of years.

The proximate causes of the recent price decline are:

- The destruction of demand in travel, tourism and transportation activities due to the Coronavirus pandemic

- The feud between Saudi Arabia and Russia for effective control of the OPEC-plus group

Presumably, these two influences may have some lasting impact, but they should nevertheless prove temporary. With regard to the Russian-Saudi feud, although the two main protagonists disagree on many points, they seem to agree, openly or not, that a lower oil price will help reduce or eliminate the threatening competition from America’s rising production of shale oil.

It seems that this part of their agenda is meeting with some success. According to brokers Wood Mackenzie, a tenth of the global oil production may become uneconomic at current prices. This would represent about 10% of the global supply, estimated at 100 million barrels per day by the International Energy Agency. Heavier oil production from Venezuela or Mexico requires prices above $55 a barrel; Canadian oil sands need $45 a barrel. RS Energy Group estimates the break-even price for oil from the best shale-producing areas is $43 a barrel. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia or Russian oil may cost $10 a barrel or less to produce. (All above data from the Financial Times, 3/22/2020)

US shale operators will suffer rapidly because their reservoirs tend to be depleted over much shorter cycles. The shale revolution allowed the US to become the world’s biggest oil and gas producer, with a record oil production of 13 million barrels a day — estimated by some analysts to shrink by 2.5 million barrels a day by 2021. Meanwhile, capital spending across the shale sector will fall from $107 billion last year to $64 billion this year, according to the consultancy Rystad Energy.

Jamie Webster, of the BCG Center for Energy Impact, summarizes his view of the situation as follows: “Shale thrives at $100 a barrel, survives at $50 and dies at $25.”

There will come a time when the Coronavirus pandemic is only a very bad memory. Meanwhile, both Russia and Saudi Arabia reportedly need oil at prices much higher than the current price-war levels in order to meet their governments’ budgetary obligations. It seems likely that, sooner or later, they will declare victory and settle on an acceptable oil price. Then, the lowest-cost and financially strongest shale producers may not “thrive” but they are likely to survive profitably after their weakest competitors have disappeared and global demand volumes have recovered.

My experience with highly cyclical producers of industrial commodities (such as copper and other metals) is that the best time to buy shares of the financially stronger companies is when the industry is losing money. The recent behavior of the oil price has not escaped the media, who shape our view of the world, as the Financial Times, among others, reminded us on 3/24/2020:

OIL INDUSTRY FACES BIGGEST CRISIS IN 100 YEARS

This may be a good time to remember the famously contrarian record of the most sensational newspaper headlines.

Second-order Look: Watch for a New Inflationary Cycle?

Price inflation is often described as “too much money chasing too few goods.” While it is clear that money and liquidity have been plentiful in recent years (quantitative easing, zero percent interest rates, etc.), it would be harder to argue that there have been too few goods available to buy. Globalization, the offshoring of production to cheaper manufacturing regions, as well as progress in productivity and logistics have made ample supplies of most goods readily and cheaply available.

On the other hand, recent experience may have radically altered the most efficient supply chains that were developed in the last couple of decades. This, and maybe some new protectionist trade policies, may reverse the race to the cheapest possible products.

Meanwhile, trillions of dollars are in the process of being injected into the world’s leading economies and further stimulus is already being planned. As I mentioned, it will be easier to spend that money than to withdraw it when it is no longer needed for non-inflationary growth.

William White, former Head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the Bank for International Settlements, and Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada, just wrote a paper for the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, in which he discusses, among other topics, the unintended consequences of past policies (OMFIF, 23 March 2020). He concludes that “It would be wrong to assume a zero threat of higher future inflation.”

The drawback of second-order thinking is that it may suggest investment opportunities for a time horizon well beyond the impact of first-level thinking. But it takes time to stand out from the crowd, and we plan, as always, to be patient.

François Sicart – March 30, 2020

Disclosure:

The information provided in this article represents the opinions of Sicart Associates, LLC (“Sicart”) and is expressed as of the date hereof and is subject to change. Sicart assumes no obligation to update or otherwise revise our opinions or this article. The observations and views expressed herein may be changed by Sicart at any time without notice.

This article is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.