Articles

SIZE, CONFLICTS OF INTEREST and FIRM CULTURE

As We Enter Our Third Year, Some Thoughts About How to Pick, and Be, the Right Money Manager

In Planning Our Life and Beyond (http://www.sicartassociates.com/planning-our-life-and-beyond/ July 10, 2018), I cited at length Dr. Leon Danco, a leading advisor to family businesses who, when I was founding Tocqueville Asset Management thirty years ago, shared with me his wisdom about planning an entrepreneur’s life.

Dr. Danco found that measuring our lifespan in months rather than in years or decades promotes a sense of urgency in taking charge of our lives. At the time, he was assuming an average lifespan of 900 months. I have updated this sum and rounded it up, perhaps optimistically, to 1100 months (92 years) in paraphrasing him here.

Learning, Doing and Teaching

In our first 300 months, what Dr. Danco calls “the learning years,” we learn and we consume: our contribution to society, aside from giving joy to our parents, is fairly minimal.

At some point around our 25th birthday, our education in the formal sense is completed and we begin to do things. We experience successes and failures. We may abandon some endeavors and embark on new ones. Whatever contribution most of us make in our lives, we do it during these productive years (about 400-450 months).

By age 60, most of our accomplishments are apparent and we are about to enter our last contributory 400 months, the teaching years.

Now in the middle of my teaching years, I plan to remain active for a good while, so in no way is this a farewell address. Nevertheless, I have reached the stage where I can formulate and share some wisdom gained from experience.

Business is a little bit like parenthood: You make mistakes, hoping that they will not be fatal either to your family or to your career, and you learn from them. I have no doubt that I am a much better adviser to our clients and their children today than I was to my children during my parenting years. (I hope that I also have become a good counselor to my partners, who are in the midst of their doing years.) One of the issues that I keep returning to is …

…The Difference Between a Client and a Sitting Duck

Unfortunately, the distinction is often just a matter of degree. If you are a potential client for financial services, be aware that everyone has something to sell you. They will usually appeal to either your greed or your fear. Over the years, financial marketing departments have been frantically inventing new products that will appeal to those two primal dispositions, by promising huge potential gains or protection against unbearable risks. In the end, however, these new products are designed to either add new clients or to retain old ones in the face of growing competition, and they must be sold. When marketing departments package new products, therefore, what is best for the client tends to be eclipsed by what is saleable.

Of course, financial marketing departments and sales people are not necessarily dishonest. But the fact is that, in finance especially, it is difficult to avoid potential conflicts of interest between a business and its clients. Many sources of such conflicts are now regulated (order front-running, insider trading, etc.), but others are more subtle.

For example, if you are a portfolio manager and also a licensed broker receiving commissions on each trade, you must decide whether you are making trades purely for the benefit of clients or if you are influenced by the additional revenue from commissions.

Similarly, if you are a portfolio management firm with your own mutual funds, the expense ratios on these funds (including management fee, custody fees, accounting fees, regulatory fees, marketing and other administrative costs) are typically quite a bit higher than the costs on a separate client portfolio. If you decide to buy one of your funds instead of separate securities in a client’s portfolio, is it for their good, for the added revenue, or to build up your fund’s assets under management?

Since new financial products are increasingly complex, clients are well advised to ask, “How are you and your firm making money on this new product?” rather than, “How much do I stand to gain or lose?” You will learn much more about the product.

Performance Incentives: In the Same Boat as Long as It Floats

My original idea for this paper was a prompted by a series of questions from new clients about incentive fees for portfolio managers.

Most traditional portfolio managers earn a fee that is a percentage of the assets they manage.

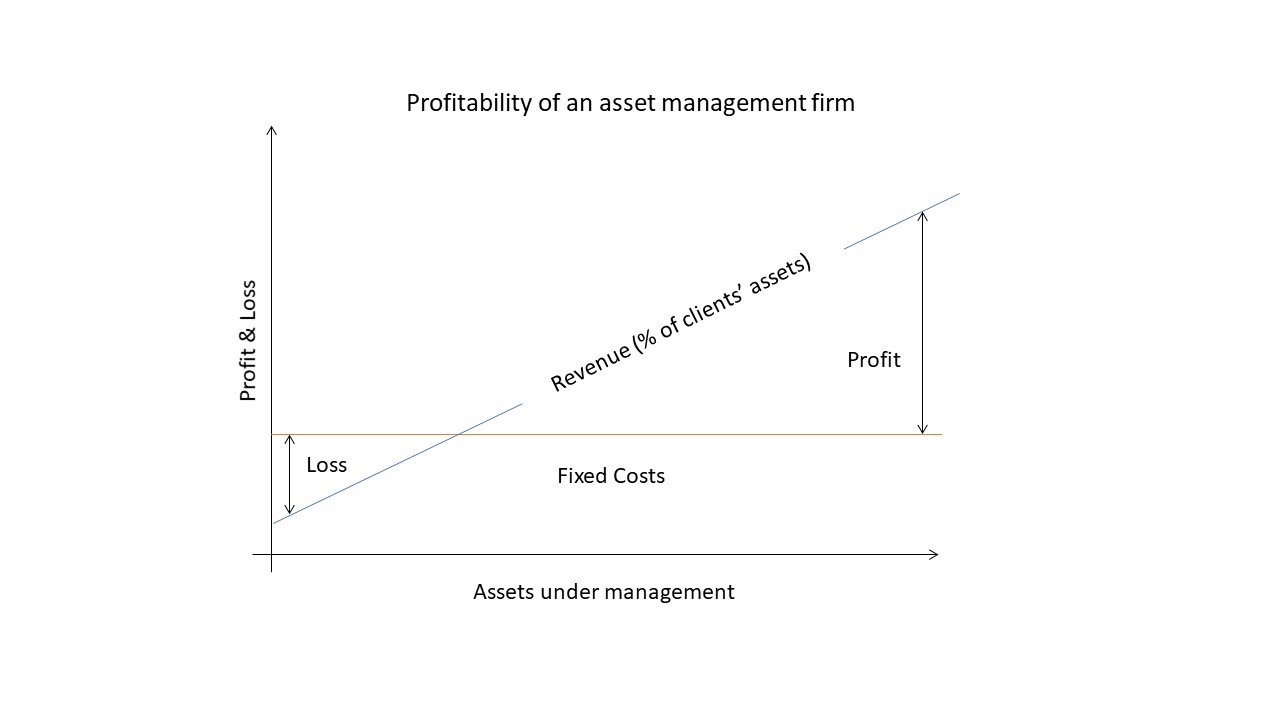

That fee fluctuates with money inflows and outflows but also, importantly, with the ups and downs of the securities markets. In contrast, most of the manager’s costs are essentially fixed (rent, salaries, research services and equipment, insurance, etc.). The result is a natural correspondence between clients’ investment performance and the profits of their managers, as this graph attempts to illustrate:

[Note: the graph excludes money coming in or leaving the portfolio so that it depicts only the impact of performance on a manager’s profits.]

Clearly, the better a portfolio’s performance, the stronger the manager’s fees. Profits, though, are even stronger since costs do not increase proportionally.

As a money manager myself, I do believe that this kind of leveraged benefit is legitimate. But this is also why I do not think that an additional incentive to perform is necessary to compensate the money manager or to put the client and his or her manager “in the same boat,” as is often argued.

Another problem with incentive fees is that they are usually based on relatively short-term performance measurements (often one year). Not only does this practice disrupt the decision-making of managers with long-term objectives but, in unfavorable market periods, it may create cash-flow problems for the manager. Incentive fees are usually combined with a relatively low, recurring fixed fee. Very often, there are so-called “high-water marks,” which prevent the manager from receiving incentive fees until the portfolio’s historical high valuation is exceeded. In the interim, the manager’s income is depressed.

When the chances of exceeding a high-water mark evaporate because of extended underperformance, a manager may be tempted to abandon that particular portfolio and go elsewhere to find new money to manage. “Heads I win, tails you lose,” — and so much for being in the same boat with the client.

Is Money Management a Business or a Profession?

At the heart of the debate about conflicts of interest in money management is how the money manager views his/her role.

A majority of money management firms now see themselves as businesses and are run accordingly. The classic business model is to increase revenue (number of products, sales volume, and prices) while controlling costs – personnel in particular. Since we illustrated earlier that, in basic money management, revenues tend to grow faster than costs over time, the main imperative of money management businesses is growth in revenues. This usually means acquiring more clients, selling them more products and charging whatever price the market will take.

On the other hand, some money management firms still view themselves less as businesses and more as offices of professionals. Here, time and talent spent on client service and enduring relationships are all-important. As a result, profits stand to benefit in a much less leveraged way from the growth in revenue, since that growth must be supported by a commensurate increase in the number and quality of professionals.

I do no want to be misunderstood. A young former intern once reported with praise: “I told some people at dinner last night that I had met a banker who does not like money.” Since he was referring to me, I had to clarify: I do like money, but I do not think that amassing it should take precedence over the satisfaction of doing things right and for the benefit of clients you are meant to serve.

This does not apply only to me. Early in my career, an attorney specializing in finance for families told me: “In private banking, the people you hire should join your organization as other people enter religion.” And indeed, traditional private banking usually offers few promotions, career advances or public prestige. Private banking employees can make more money than those in commercial money management, but they will usually remain in the same position for the rest of their careers, because that is what loyal clients want. Their main reward, then, is the diversity of challenges, the satisfaction of providing great service, and the gratitude of clients.

The model I have personally tried to embody at Sicart Associates is that of the 19th-century “homme d’affaires” – an experienced generalist who manages the fortunes of one or a few families with great competence and loyalty. This individual can also deal with outside experts on behalf of his clients when needed, because he understands the families’ needs as well as (or sometimes better than) family members themselves

What Is More Than Enough?

When I reflect about our firm’s purpose, I am often drawn back to Charles Handy’s seminal book The Hungry Spirit (Broadway Books 1998). It starts thus:

“In Africa, they say there are two hungers … The lesser hunger is for the things that sustain life, the goods and services and the money to pay for them, which we all need. The greater hunger is for answer to the question ‘why?’, for some understanding of what life is for.”

Later in the book, Handy explains that each of us has a threshold of material comfort when he or she can say “I now have enough and more would not necessarily add to my quality of life.” This threshold can be higher for some than for others, which is fine, but everyone should have one. Once that point is reached, we must search for other sources of satisfaction and fulfillment.

One of the advantages of the distinction between the two hungers is that it can apply to both our personal and our professional lives. And in fact, it is a good start to reconciling the two.

Sicart Associates: Onto our Third Year and Beyond

I have worked with the remarkable individuals I hand-picked as my partners in Sicart Associates for a decade and more. I no longer have much to teach them in terms of financial analysis or patrimony management: they are at least as skilled as I am and probably more so. What I can do is share my personal experiences on specific problems similar to those I have encountered in the past. I can also, I hope, help instill a lasting culture in our firm. I would like that culture to be one that reconciles the two hungers.

For a firm like ours, I believe that implies controlling our size and thus accepting limits on our growth. We will be the best stewards of our clients’ fortunes if we work in a congenial and caring atmosphere, where there are neither competing agendas nor internal politics. As I have experienced elsewhere, this balance would be harder to preserve once the team number grew too large.

Controlling growth might be interpreted as abandoning ambition, but nothing could be further from the truth. Some of our partners may have reached their material “enough” but others are still only approaching it. Anyway, the meaning of the greater hunger for Sicart Associates, rather than aiming only for more, should be to aim lastingly for better and its own rewards.

In investment research, where there is now too much rather than too little information, more brains are not essential. Shared discipline, compatible time horizons, patience and character (a combination easier to achieve with compact teams), are keys to long-term performance. I remember that many of my best investment ideas date back to the time when I worked intimately with only one close partner: the late and missed Jean-Pierre Conreur, whom some of my partners and many of our clients still remember fondly.

In matters of family patrimonies, support teams (lawyers, accountants, tax experts) are crucial but it is better to have a choice of the best-suited for each situation than to try to have all these capabilities in-house where their use might be a source of conflict of interest. But, for experts to operate at their best and in synergy with each other, a capable and experienced generalist, thoroughly familiar with the intricacies and needs of client families, is necessary to sort out the challenges and problems before presenting them to the experts.

In the end, a small team, focused on what we do best, without dilution from other products or services, is our best hope to sustain a culture of “hommes and femmes d’affaires,” for the continued benefit of our clients.

* * * *

Finance is not merely about making money. It’s about achieving our deep goals and protecting the fruits of our labor. It’s about stewardship and, therefore, about achieving the good society. — Robert J. Shiller

There’s more honor in investment management than in investment banking. — Charlie Munger

François Sicart

September 8, 2018

Disclosure:

This article is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.