In a previous paper (http://sicartassociates.com/would-the-real-economy-please-stand-up/), I argued that policy makers are being increasingly misled by statistics that were created to measure the 20th-century industrial economy. Our more virtual, 21st-century economy is hard to capture with such obsolete methods. I concluded with a question, which I promised to answer in a forthcoming paper:

“Faced with contradictory indicators that seem to be confusing policy makers, what should investors do?”

My intuitive answer to such a question would be: “Nothing special.” Many observers, ourselves included, believe that there is little usable correlation between the growth of economies and their stock markets’ performances.

Economy and Stock Market: A Very Independent Relationship

Renowned economist and 1970 Nobel Prize winner Paul Samuelson famously quipped that: “The stock market has called nine of the past five recessions.”

Indeed, the correspondence between the strength of a stock market and the health of its economy is not what the public generally assumes. One of the best-known studies on the subject was done by Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton at the London Business School in 2005. They examined 17 countries over more than 100 years and actually found a negative correlation between investment returns and growth in GDP (Gross Domestic Product) per capita:

“Historically, buying into equity markets with a high GDP growth rate has given a return that is below the return of markets with a low GDP growth rate. There is no apparent relationship between equity returns and GDP growth.” (Global Investment Returns Yearbook, 2005)

More recently, according to the New York Times (“The Economy and Stocks: A Big Disconnect” 12/16/12), the Vanguard Group looked at equities’ returns going back to 1926. They examined the predictive power of important variables such as price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios, growth in GDP and corporate profits, past stock market returns, dividend yields, interest rates on 10-year Treasury securities, and government debt as a percentage of GDP. Their conclusion was that “none of these factors come remotely close to forecasting accurately how stocks will perform in the coming year”.

“Even over a 10-year time horizon, considered by many investors to be long term, only P/E ratios had a meaningful predictive quality.”

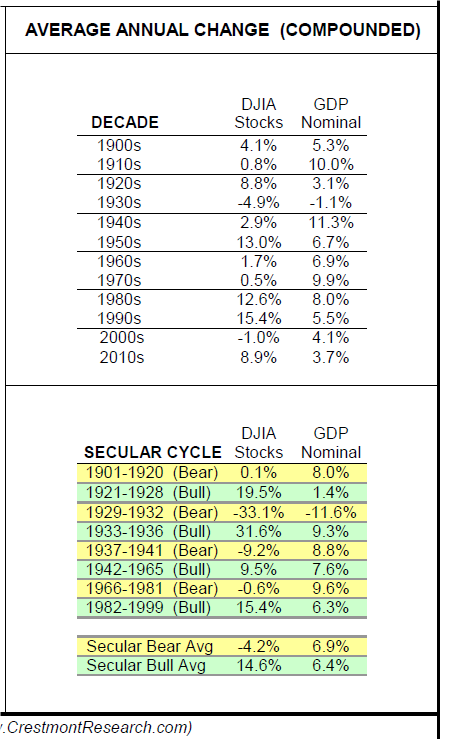

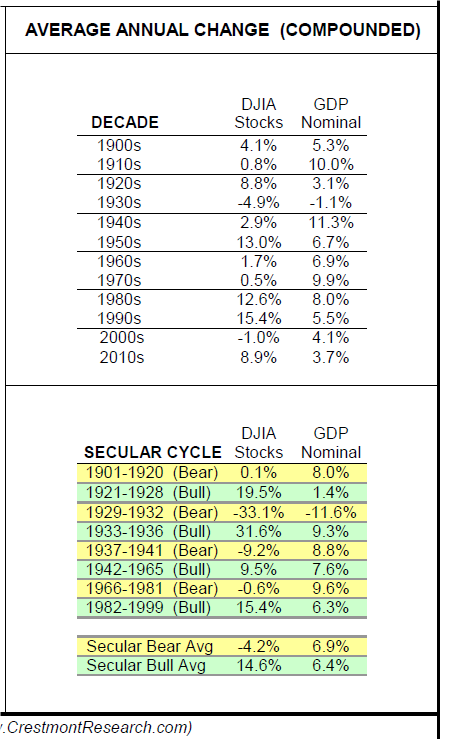

With a narrower focus on just the US market, Crestmont Research compared GDP growth and the change in the Dow Jones Industrial Average (without dividends) decade by decade and also for selected secular bull and bear cycles through 2015.

The disconnect between economic growth and stock market performance is inescapable.

Source: Crestmont Research

Looking for Wisdom Outside of Economics

Early in my career, an economist at the US Federal Reserve consulted me about opening an account with my firm, Tucker Anthony, because she realized that “economists usually do a poor job of managing their own investment accounts.” The same realization may explain why the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences was awarded to Daniel Kahneman — a psychologist!

I have long been fascinated by the relatively new discipline of behavioral finance, also popularized by researchers such as Richard H. Thaler (Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics, 2015) and Robert J. Shiller, another Nobel laureate (Irrational Exuberance, 2000). Kahneman’s book (Thinking Fast and Slow, 2011) on the psychology of judgment and decision-making is full of profound and entertaining insights, including many about investing. For instance:

Hindsight, the ability to explain the past, gives us the illusion that the world is understandable… We should accept the world is incomprehensible much of the time… You can protect against certain scenarios better than you can predict them.

Many individual investors lose consistently by trading — an achievement that a dart-throwing chimp could not match…

Unfortunately, Prof. Kahneman is not impressed by the competence of investment managers either:

For a large majority of fund managers, the selection of stocks is more like rolling dice than like playing poker.

There are domains in which expertise is not possible. Stock picking is a good example. (Time Magazine – 11/28/11).

It is wrong to blame anyone for failing to forecast accurately in an unpredictable world. However, it seems fair to blame professionals for believing they can succeed in an impossible task.

Some Investors, Including Professionals, Consistently Fail to Perform

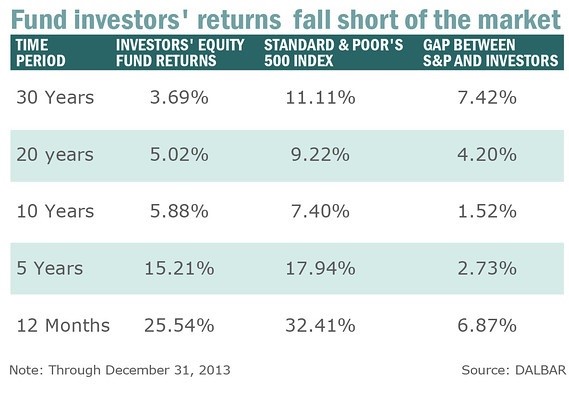

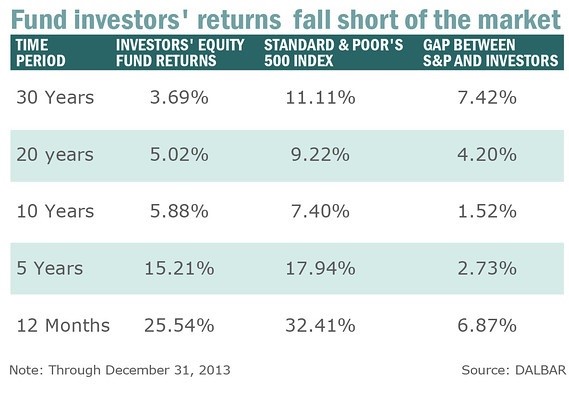

It is no secret that most professional investment managers fail to equal the performance of their benchmark indices and that many individual investors actually lose money over long periods. Performance-measurement firm DALBAR tracks mutual fund purchases and redemptions by investors to calculate the actual returns earned by these investors, with the following results:

The following press extracts also confirm that most investors underperform the main stock market indices over time:

In Europe, 86 per cent of active equity funds failed to beat their benchmarks over the past decade, according to S&P’s analysis of the performance after fees of 25,000 active funds. (Financial Times – 3/20/16)

According to S&P Dow Jones Indices, 82% of large-cap funds generated lower returns than the S&P 500 in the latest 10 years. (USA TODAY– 3/14/16)

Despite this evidence, I respectfully disagree with Prof. Kahneman. If a majority of investment managers fails to equal or beat their benchmarks over relevant periods of time, it must mean that a minority does achieve that goal.

Of those, no doubt a few possess exceptional skills that common mortals do not. Their results would be hard to replicate. But I usually try to follow the advice of Warren Buffet and Charlie Munger, which they learned from nineteenth-century mathematician Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi’s advice for solving problems: “Invert, always invert.”

In our case, that inversion means not seeking out popular stocks for their potentially big returns. Instead, we should concentrate on avoiding the mistakes that cause the majority of stock market losses.

What are (some of) those mistakes?

The Mythology of Investment Success Can Be Dangerous to Your Wealth

One common error is viewing the stock market as some magical box that can be unlocked by discovering a secret formula. Another is the belief that the stock market is constantly being manipulated by obscure forces beyond the common man’s control. More routinely, some clients expect their investment advisers to be omniscient, with a special gift for predicting the future.

These attitudes derive from what an early mentor of mine called “the quest for certainty in an uncertain world” – by definition a hopeless endeavor. In fact, one of the first precepts of investing is (or should be) that there is no certainty in investment. This is why we diversify our holdings.

The title of a 2014 book by strategist Ned Davis asks what should count most for investors: Being Right or Making Money?

If the main goal of diversification is to avoid being hurt by rare but unavoidable mistakes, then a useful investment goal would be a good “batting average” rather than a few “home runs.” The batting-average approach seems particularly appropriate to me, because it calls for common-sense discipline and avoids the dangerous tendency to be lured by narrative. One can lose a lot of money on “good companies” or “good stories” if stocks are not bought at the right price. But how to determine the right price?

Dollar Quotes Are Not an Accurate Measure of a Stock’s Popularity

The stock market is an auction process, i.e. the price of a stock is determined by the bidding tussle between buyers and sellers. In the very long term, it can be argued that stock prices will grow with corporate profits. But over shorter periods of several years, the stock market is volatile and functions, frankly, more like a popularity contest.

To understand this, it is important to realize that the quoted price of company’s stock is meaningless in itself: it only has significance when compared to some fundamental value of the underlying company. For instance, the price/earnings ratio enumerates how much investors are willing to pay for the portion of that company’s earnings accruing to one share of stock. Note that price/earnings ratios give no precise signal to buy or sell a stock. But numerous studies have demonstrated that fluctuations in stock prices are caused more by changes in price/earnings ratios than by changes in earnings alone.

Furthermore, buying stocks at low price/earnings ratios results in better investment gains in the ensuing 10 years or more than buying at higher price/earnings ratios.

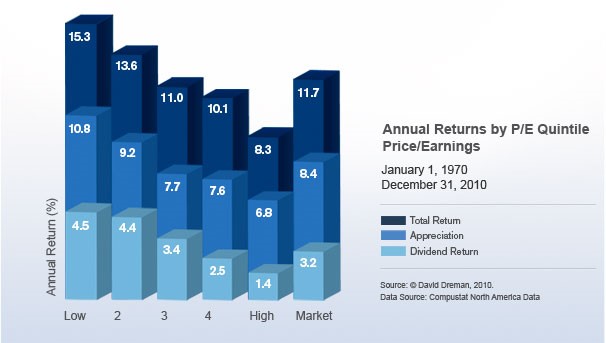

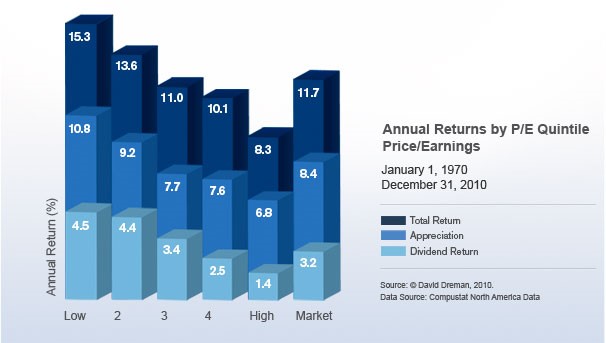

For example, Dreman Value Management measured the performance of the 500 largest US companies between 1970 and 2010. Here is what they found:

Including dividends, stocks with the lowest 20% of P/E multiples increased 15.3% annually, while stocks with the highest 20% of P/E multiples increased 8.3% annually, on average. The sample average, which closely tracks the S&P 500 Index, returned 11.7% annually during the same period.

When one looks at the compounded returns, the difference is staggering. An investment of $1,000,000 in the lowest P/E group in 1970 and switched annually would have ended up at $327 million at the end of 2010, compared to $26 million for the highest P/E group.

This corroborates our earlier comment: the batting average of investing in stocks with low price/earnings ratios should be better than the batting average of investing in stocks with high price/earnings ratios. And overall, investing in stocks with high price/earnings ratios tends to lower our odds of achieving excellent returns.

Putting Some Horse Sense in Investing

We cannot forget that fluctuations in price/earnings ratios are dictated principally by emotional and psychological factors. This is why, without assimilating it to gambling, stock market investing can in many ways be compared to betting on horse races. Expectations clearly differ from fundamentals when betting on horse races; they also do in the stock market. Michael J. Mauboussin explains, in The Success Equation (2012):

The fundamentals are how fast a horse is likely to run. A handicapper might estimate that based on factors that include the horse’s past finishes, the track condition, the jockey, the distance, and the strength of the field.

The expectations are the odds on the tote board, which can be translated into a subjective probability of a horse’s likelihood of winning…

[But] making money through betting on horses is not at all about predicting which ones will win or lose. It’s about picking the ones with odds—or a price— that fail to reflect their prospects—or value. In other words, [those where] expectations are out of sync with fundamentals.

Being Guided by Price/Earnings Ratios Improves Our Potential Returns

Valuation can help improve the timing of our exposure to the general market as well. In 1988 Harvard economist John Y. Campbell and Yale economist Robert Shiller developed a cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (CAPE), which divides the current market price by the average inflation-adjusted profits of the previous 10 years (to attenuate the impact on earnings of the business cycle). Their work showed that for the general market, too, periods of high valuation tend to be followed by years with low returns and are better avoided, while periods of low p/e ratios are more propitious to investment, on a 10-year horizon:

“It’s in The Price!”

“It’s in The Price!”

The nature of an auction process is that the more broadly the object offered is desired, the higher its price goes. In the stock market, the better the fundamental story is, and the more widely it is known by the public, the higher the price/earnings ratio will be. This is why the odds of making money get worse as a stock rises: as old pros will warn you, by the time the story about a great company reaches you, it is likely that that story “is already in the stock’s price.”

In The Four Pillars of Investing (2002), William Bernstein reminds us that exciting investments are those that have attracted the most public attention and are thus “over-owned” In other words, their fame has attracted excess investment dollars. This drives up their price, thus lowering future returns:

… purchasing the past five or ten years’ best-performing investment invariably reflects the conventional wisdom, which is usually wrong.

… more times than not, the purchase of last decade’s worst-performing asset is a much better idea.

… In investing, the most exciting assets tend to have the lowest long-term returns, and the dullest ones tend to have the highest.

“Dare to be dull,” Bernstein advises… “A superior portfolio strategy should be intrinsically boring. If you want excitement, take up skydiving or Arctic exploration.”

Hubris, Naiveté and Marketing

In Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman explains why experts always seem so confident:

Experts who acknowledge the full extent of their ignorance may expect to be replaced by more confident competitors… An unbiased appreciation of uncertainty is a cornerstone of rationality—but it is not what people and organizations want. Extreme uncertainty is paralyzing under dangerous circumstances, and the admission that one is merely guessing is especially unacceptable when the stakes are high. Acting on pretended knowledge is often the preferred solution.

Investing under the illusion that certainty exists in our uncertain world is dangerous. In the current environment, uncertainty reigns. In a recent paper, I concluded:

No matter who won the elections, the task of the new President was bound to prove very challenging… The continued conflict between the forces of inflation and recession will likely intensify somewhat under a Trump presidency and we believe that keeping ample cash reserves remains the wise position for investors, especially at current valuation levels.

(http://sicartassociates.com/between-inflation-and-deflation/)

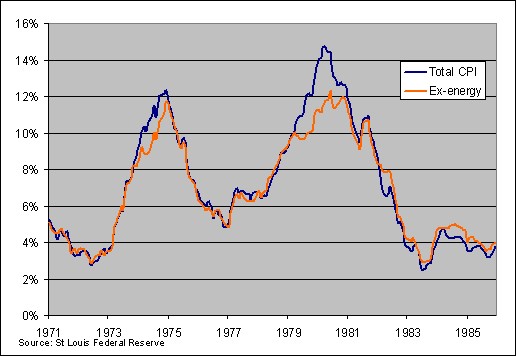

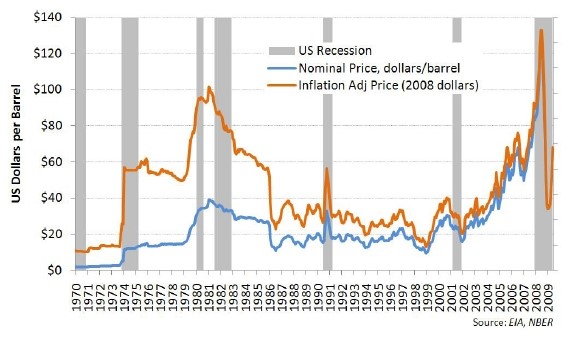

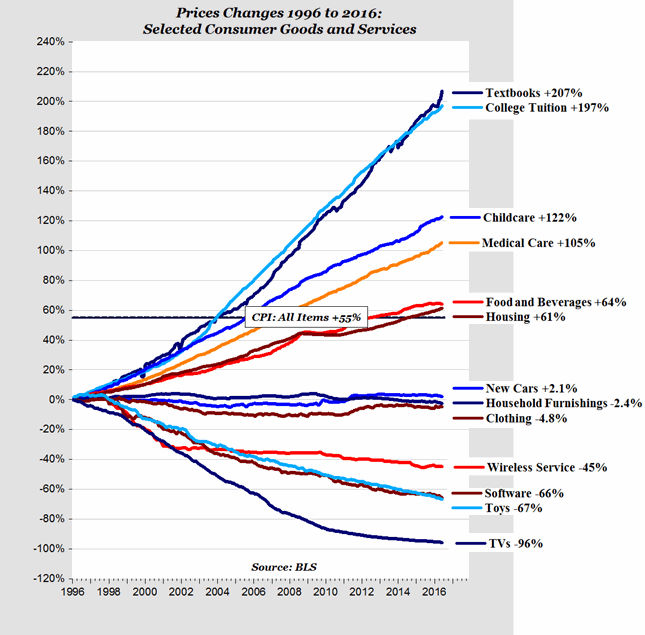

We now know that under Mr. Trump’s presidency, expansive fiscal programs run the risk of re-igniting inflationary pressures in an economy that, despite statistical confusion, is close to full employment. At the same time, promised mercantilist and protectionist policies are reminiscent of the deflationary ones that preceded and caused the global Great Depression, in the 1920s.

With today’s delicate balance between powerful forces of inflation and deflation, no one can credibly forecast the future. If the initial weeks of a Trump presidency have indicated anything, it is that erratic policy-making — in an environment where every decision has consequences to the second, third level and beyond — holds the promise of increased financial volatility.

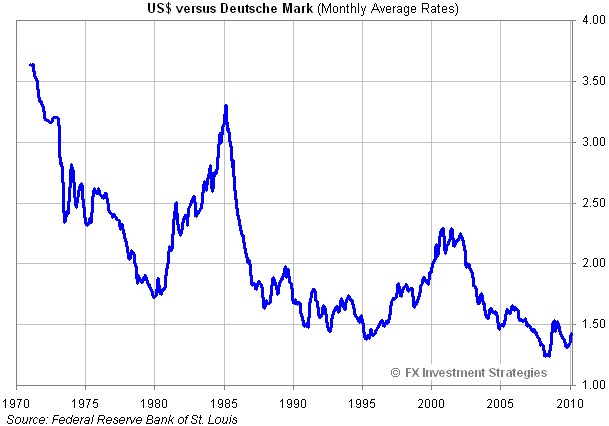

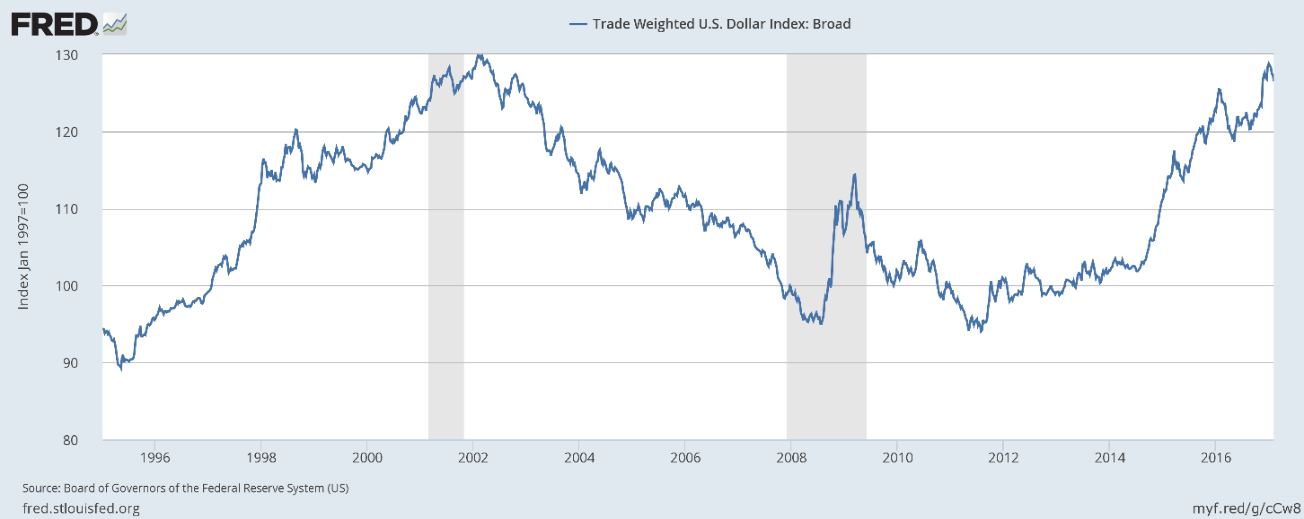

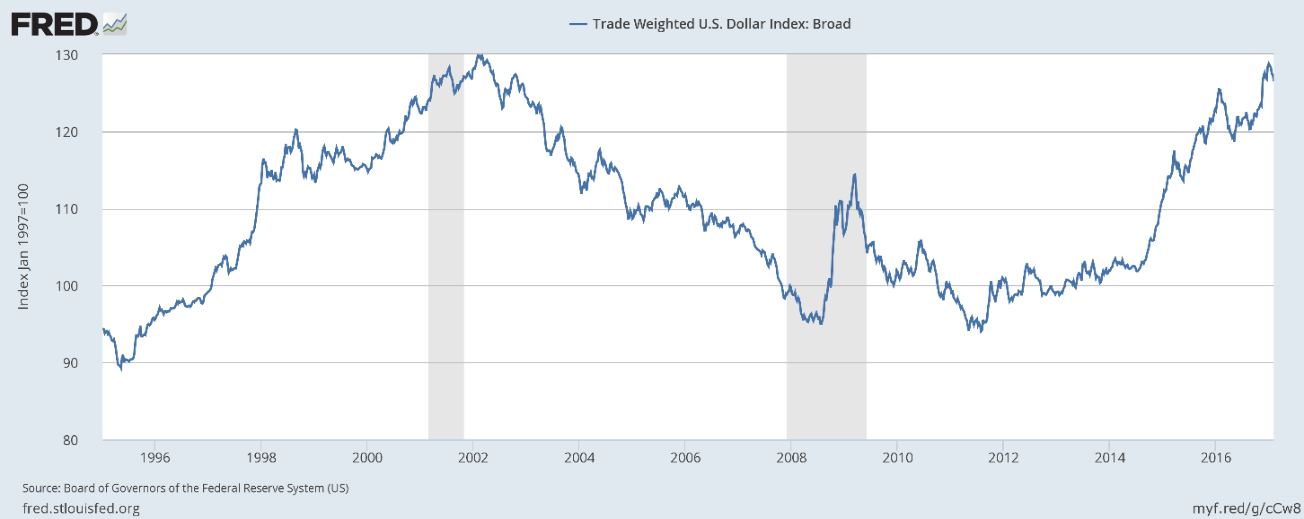

For example, since no one really knows which countries might get hurt by America’s protectionist tendencies, the dollar has risen strongly since 2015, to reflect its potential position as a refuge currency.

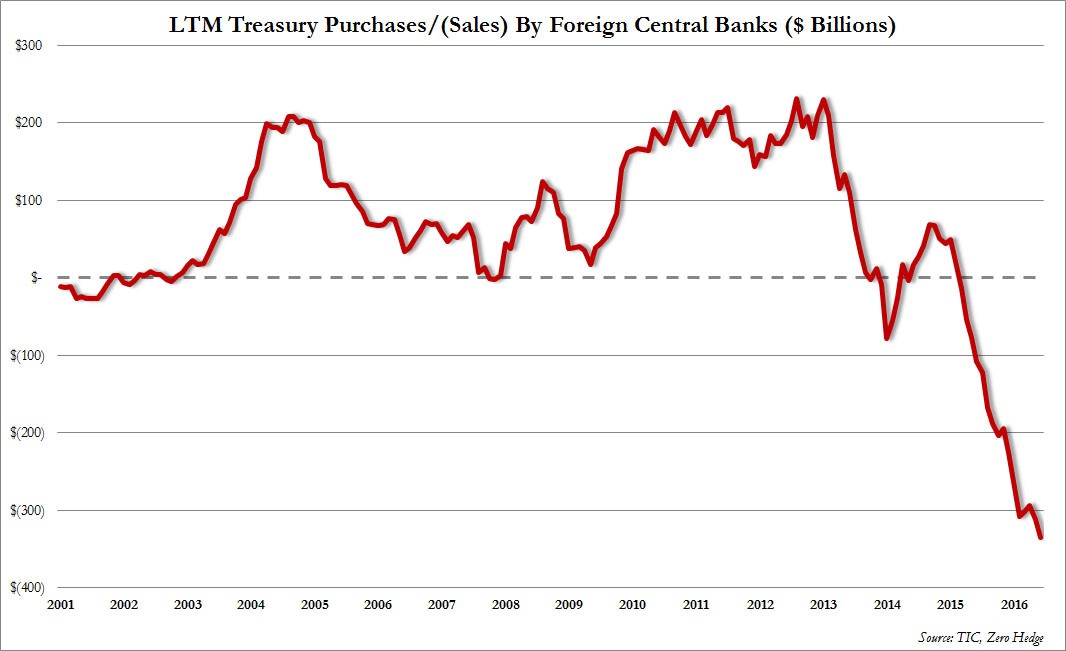

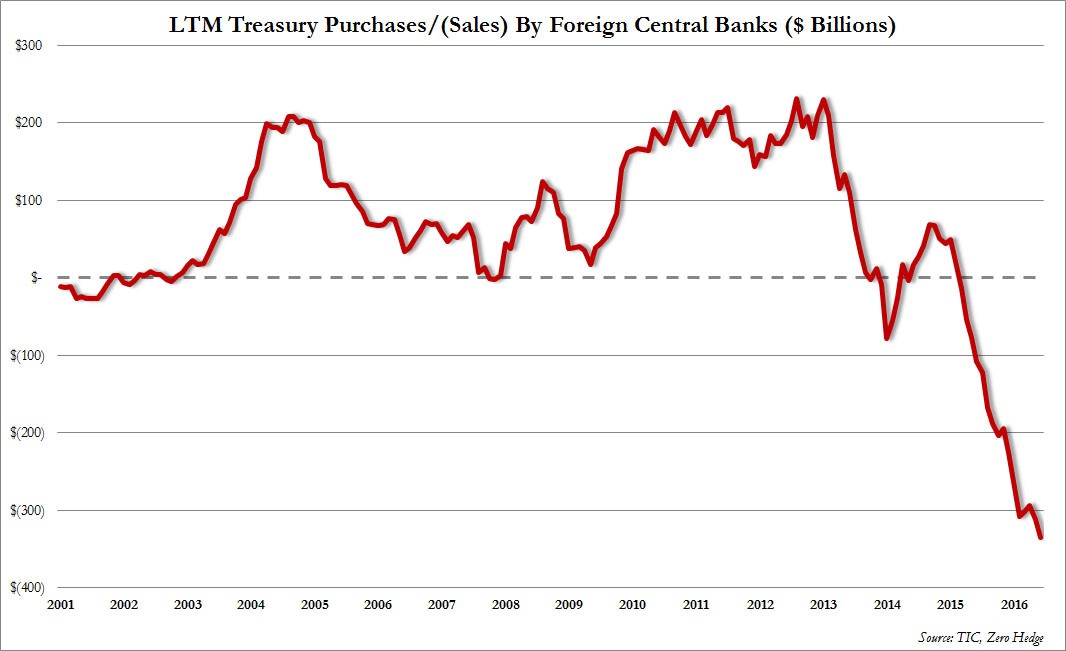

More recently, however, large foreign holders of US debt (Treasuries), including China, seem to have become aggressive sellers of dollars.

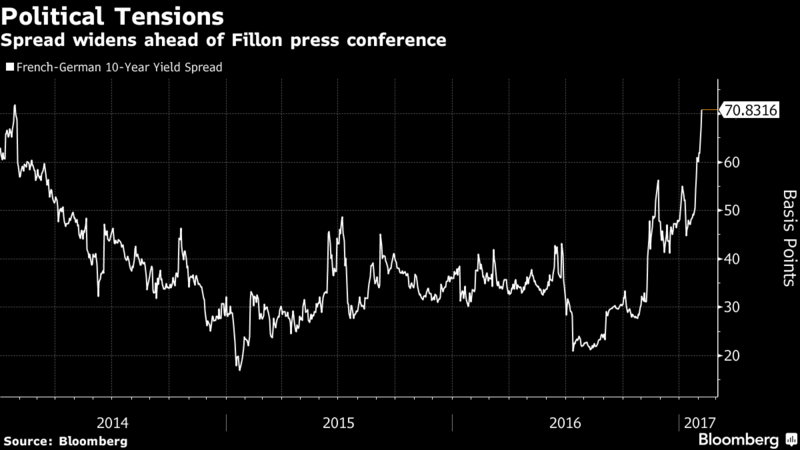

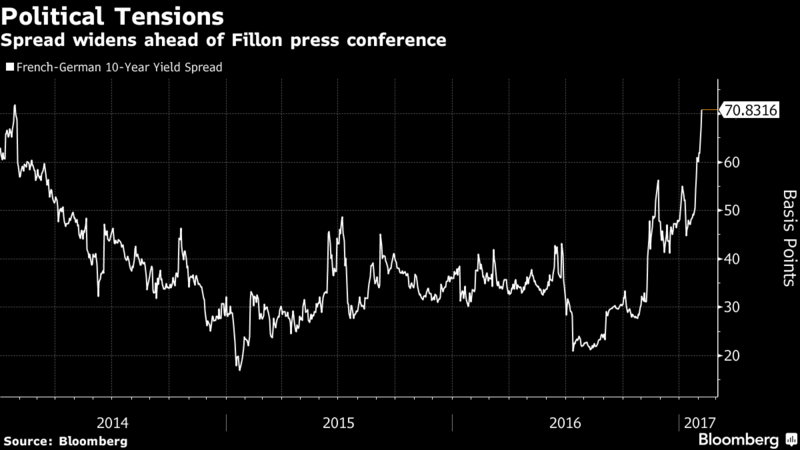

Uncertainties exist elsewhere as well. For example, reflecting election jitters and low (but not nonexistent) odds of a French exit from the Euro, spreads of French interest rates over those of other Euro debt have spiked to levels not seen in recent years.

Meanwhile, unstable foreign exchange and interest rate markets are potentially harmful to large banks, such as Deutsche Bank, which has encountered recurring problems. Recently, Deutsche Bank AG bought full-page ads in all major German newspapers to apologize for “serious errors” after misconduct costs helped tip the company into two years of losses.

Conclusion

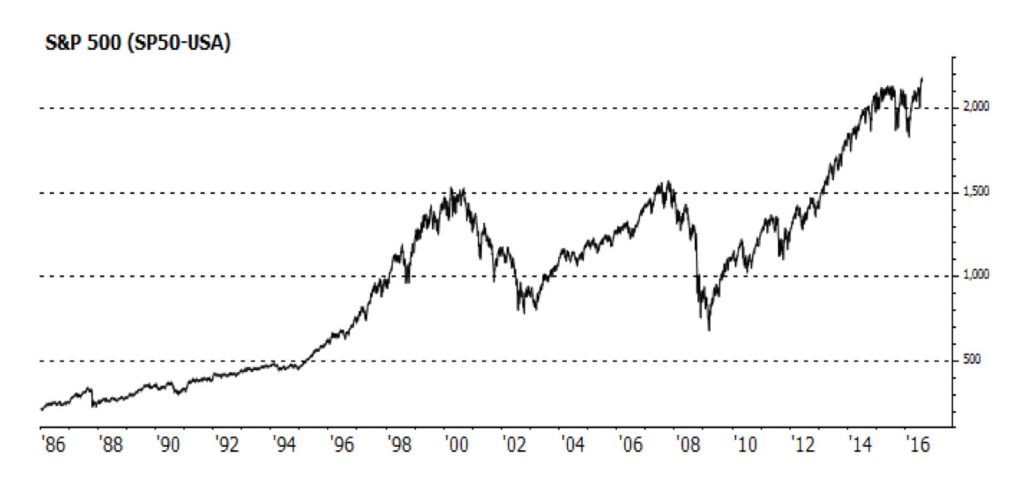

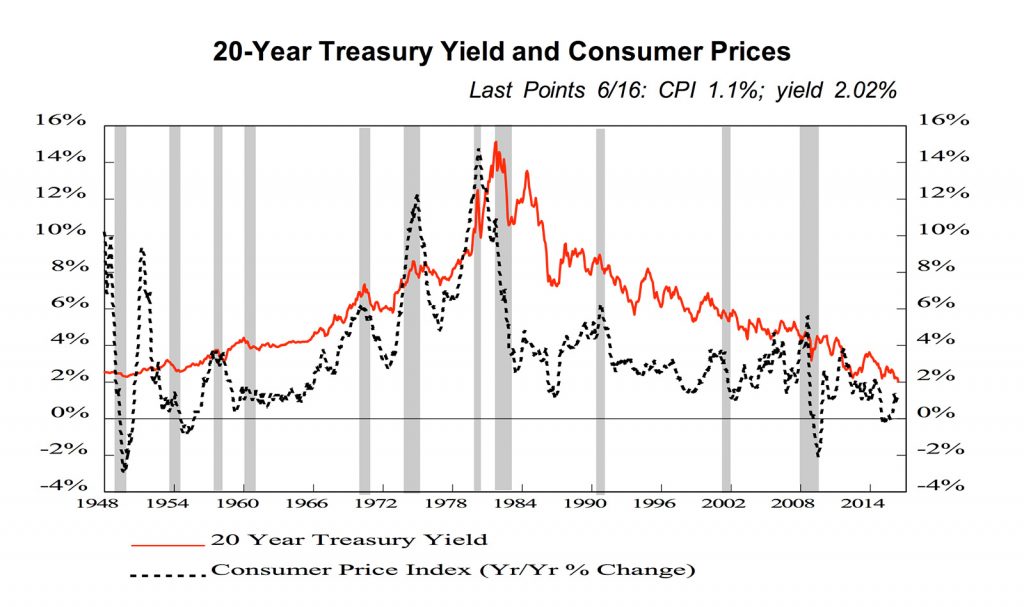

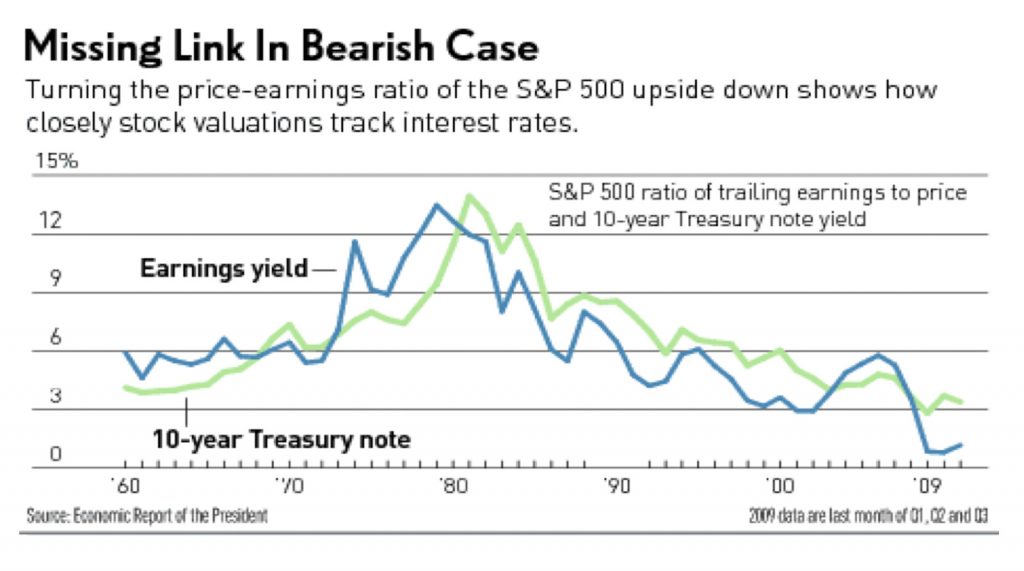

In our view, global stock markets currently offer few compelling values. Optimists argue that historically-high price/earnings ratios are justified by historically-low interest rates. But investors who do not enjoy dancing on top of volcanoes cannot ignore that record-low interest rates are usually followed by higher ones.

Erratic policies in the United States, and possibly in other countries facing changes in governments, are likely to trigger changes in expectations and thus increased volatility in price/earnings ratios. Yet experienced investors often view volatility as opportunity. If higher interest rates prompt lower price/earnings ratios, those of us who seek out value – and a few base hits to boost our batting average – may see new possibilities in the market.

One cannot forecast the future but ample cash reserves with, of course, minimal levels of financial leverage, remain the best way we can think of to be ready for it.

François Sicart

2/16/2017

Disclosure:

This report is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.

“It’s in The Price!”

“It’s in The Price!”

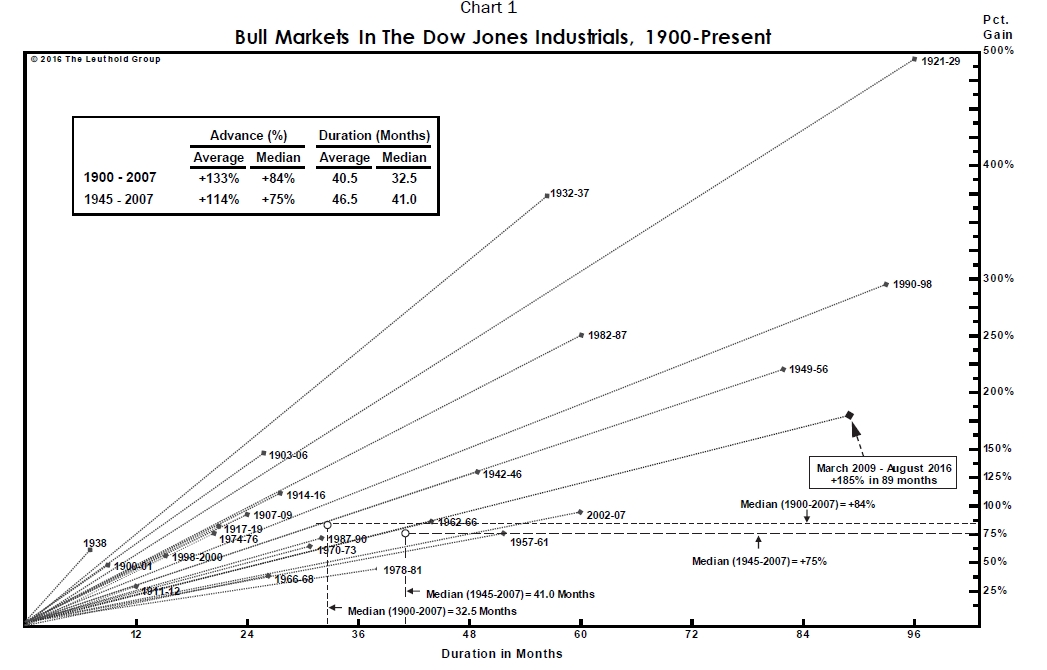

Source: The Leuthold Group

Source: The Leuthold Group