What if you could write a letter to a younger self today? What if an older self could write to you today? What would you write? What would you like to hear? I’ve been wondering about those questions both as an investor and an individual. Why? Maybe it’s the end of summer mood; perhaps it’s many conversations with young, aspiring professionals I’ve had in the last few months.

The inspiration for this essay came from several directions. First, I spoke with a good friend, Tom Morgan (Curiosity Sherpa to Billionaires), about the idea of a future self-guiding us today on our path. Then, I exchanged emails with the author and UCLA professor Hal Hershfield about his book: “Your Future Self”. Finally, with Jordan Olmscheid from The Wealth Letters I discussed the idea of a letter to a younger generation.

Tom Morgan writes: Our “future selves” may indeed use our attention and passions to direct us towards manifesting our unique potential. We aim our curiosity at the “thing of the highest value.””

Professor Hershfield shares: “People who are able to connect with their future selves, however, are better able to balance living for today and planning for tomorrow.”

Jordan Olmscheid has been collecting “The Wealth Letters,” which rely on The Wisdom of Crowds to build a framework for finding true wealth.

Writing this letter, I also thought of my earlier conversation with John Soforic, the author of “The Wealthy Gardener: Lessons on Prosperity Between Father and Son”.

***

Back to the question — what would I say if I stood in front of my 21-year-old self, who was attending a highly regarded business school in Poland, about to study abroad in Brussels, the “capital of Europe,” had his mind set on a prestigious graduate school in Paris, and was soon to start a search for an internship in New York City?

I’d say: Everything is going to be alright. Would that be wise to say, though?

Life and investing are about what we want and what we don’t want — success and failure, in a sense. It’s not always certain that what we think we want is good for us, though, and even that it’s something we will actually want when we get it. Similarly, an unpleasant experience can sometimes be more beneficial than a warm pat on the back. Life can be funny this way.

I rediscovered a great quote from Jim Carey in the beautiful book “The Sketchbook of Wisdom” by Vishal Khandelwal (special thanks to Hari, thank you for shipping a copy to me half a globe away!):

“I hope everybody could get rich and famous and have everything they ever dreamed of, so they will know that it’s not the answer.” – Jim Carrey.

What is the answer, Jim? It’s much more nuanced.

Principles

When it comes to investing, you’d think I’d like to know the top 5 best-performing stocks and put all the money in them. I think what would be better is a collection of timeless principles. Why?

For many reasons, first of all, those principles could serve me well over many decades and through all kinds of markets. Second, I think I’d have a lot of doubts about a list of five stocks shared with me by an alleged future self. Lastly, I know I could test the principles, while 5 stock recommendations without any context would be hard to hold on to for a long time.

If I had a brief moment with my younger self, I’d share what I heard growing up: work hard, be honest, and be kind. If I had another moment to distill money and investing wisdom, I’d say: live below your means and invest the rest.

Purpose

I don’t know where it came from, but I’ve always had a very clear sense of purpose. My family tells me that I have always been on a mission.

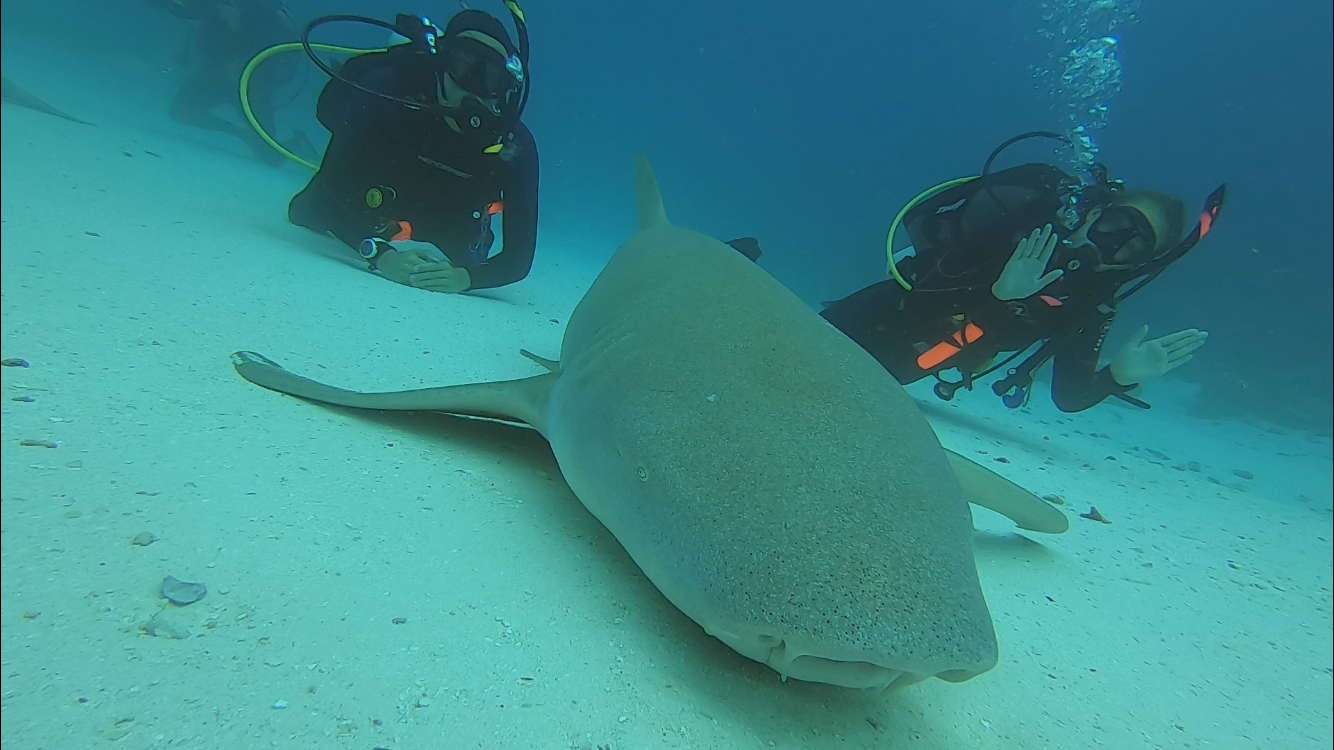

I find it helpful to be both grateful and happy with what I have today, yet I feel a constant appetite for more. I call it curiosity. That’s what leads me to another book, another stock, another adventure. The more I read, the more I want to read, and the more I realize how much more there is to know, or in other words – how much I don’t know yet! The more stocks I have researched, the more business models I discover. The more I see of the world, the more I know there is to see.

That kind of humility keeps my enthusiasm in check when it comes to investing. I’m cautiously optimistic but with a healthy dose of skepticism, always ready to ask that one more question.

Patience

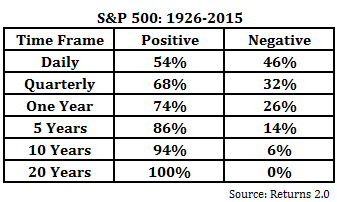

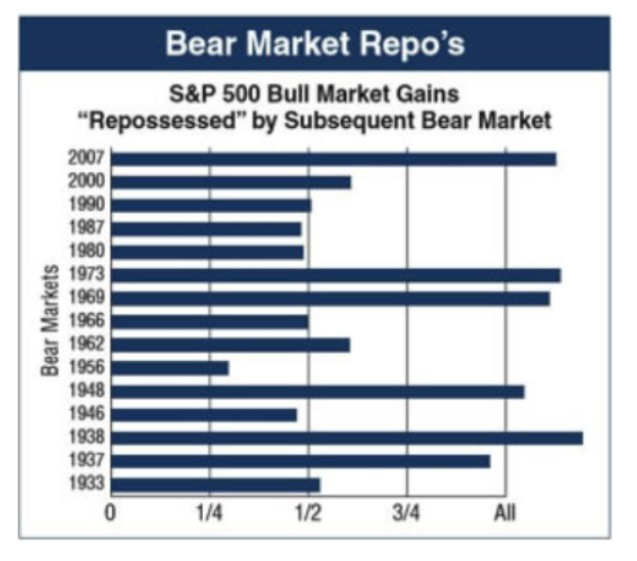

I’ve always been more patient than most people I knew at any given time. I’m not sure if it’s my nature or upbringing. I think both. I wasn’t always sure that patience is a good quality, either. Maybe in some endeavors, waiting is detrimental in the spirit of “you snooze, you lose.” In investing, it’s NOT usually the case, though.

Looking back, I didn’t grow up around same-day delivery, instant shopping, and entertainment; everything took time, and most things didn’t work as hoped right away. Even computer games took a while to load, not to mention early websites. In the real world, I remember planting vegetables and trees growing up. I knew that waiting was part of the game. Patience was the only way.

Only this week, in my podcast recording with Brian Feroldi (financial educator, YouTuber, author). we spoke about patience being the only edge that investors have over Wall Street. I call it the last arbitrage — time arbitrage. I often share that I’m probably not smarter or faster than most, but I do my best to be more patient. You’d be surprised how any competition quickly fades away when you are willing to stay that extra hour or an extra year.

Christopher W. Mayer (best-selling author, and investor) shared with me the idea of a delayed reaction. Many might be familiar with delayed gratification – the now almost proverbial waiting for the second marshmallow. Chris’ point is very helpful, though, even life-changing. In moments when a lot is at stake, a quick reaction might get us in trouble. A deep breath, a pause, and the extra thought can make all the difference. Sometimes, the best we can do is sleep on it.

In the service of others

I was raised around some great examples of lives well-lived. In my family, we have had doctors, teachers, accountants, engineers, and a senior citizen home builder and long-time manager. In a household with two doctors, often on-call and away from home, I knew that serving others is important. In the first decade of my life, in Soviet-era Poland with the Cold War reality, my parents, as physicians saving lives, were paid less than the hospital electrician – with all due respect to electricians. An arbitrary payscale ruled the day. I know that money wasn’t their motivator; it was a higher calling to serve others.

My grandmother’s second career as a builder and manager of a senior citizen home taught me about putting others first. While her contemporaries were ready to take an early retirement, she stepped up to a new role, which she found even more fulfilling than her earlier accounting career. I’m not sure which position was more beneficial on a monetary level, but I don’t think she ever cared. She answered her true calling, though it came later in her life.

***

Thinking about a letter to a younger self, I ponder what would be both timeless and impossible to misunderstand. What if I could only pass on a handful of words? I’d say follow principles that have worked for others in life and in your field. Keep your purpose alive and well throughout your life. Nurture your patience; it will save you from trouble and open up doors to wonderful opportunities. Remember that as much as you might enjoy what you do, do it in the service of others. If it pays well, it’s a bonus, but not a reason in itself. Money motivates us only that far, but to go further, we need to follow our true calling.

On another note, I can’t help but wonder — if I had indeed told my younger self that everything would be all right, would I study a bit less, work a little less hard, send fewer applications, read fewer books, research fewer stocks, etc… Would that marginal easing on the pedal make a difference? There is no way of knowing. I think that this healthy combination of excitement and nervousness, fueled by uncertainty and hope about the future and propelled forward by passion and curiosity, has proven to be a great driving force that has kept me going for a little over four decades of my life.

What I do know for sure is that the last thing I’d like my future self to do is to give me all the answers and erase all the challenges and struggles. It would take all the fun away. I’d rather know I tried hard and failed miserably, only to be ready to try again with an equal or bigger enthusiasm.

What about today? After almost twenty years in the investment profession, countless stock picks, a few books, a podcast, many world travels, many friends, and many experiences, what’s next? I’m curious what my future self would have to tell me. Everything is going to be alright? I’d prefer to hear: remember — the principles, the purpose, patience, and being of service to others. I trust that this timeless advice can guide everyone well as much as it continues to guide me, and everything has to be alright in the end.

What about your future selves?

Happy Investing!

Bogumil Baranowski

Published: 9/28/2023

Disclosure:

The information provided in this article represents the opinions of Sicart Associates, LLC (”Sicart”) and is expressed as of the date hereof and is subject to change. Sicart assumes no obligation to update or otherwise revise our opinions or this article. The observations and views expressed herein may be changed by Sicart at any time without notice.

This article is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.