HUBRIS AND FAILURE: SOME USEFUL INVESTMENT LESSONS

Last year, French journalist Christine Kerdellant wrote a book with an intriguing title (Ils se croyaient les meilleurs – Éditions Denoël 2016), which could be translated as: “They thought they were the best – a history of great management mistakes.” In the introduction, Kerdellant sings the praise of failures as marvelous learning and character-building experiences. She mentions, among others, the early stumbles of Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and Baron Bich of disposable razors and lighters fame. She also points out that Google is a veritable failures machine, where more than 70 projects per year never get beyond the project stage: “To have one of the world’s largest stock market capitalizations and some of the fattest profits and at the same time to exhibit one of the planet’s greatest number of failures is not only not incompatible but this last point probably explains the first one.”

The point is that the most successful entrepreneurs are those who have first stumbled, but have learned from their mistakes. Interestingly, they often are more prone than professional managers to search out and hire collaborators who also have experienced failure and have survived. The book appealed to me because, in Sicart Associates’ business of wealth and investment management, mistakes are quite useful — on the condition that they don’t recur too often, and that lessons are learned from them.

A few years after I created an international value fund at my predecessor firm, in the early 1990s, the fund had a very good year. A young journalist asked me in an interview, “How does it feel to be this year’s best performing international fund?” To which I answered: “First, it helps to have had a lousy year last year.” In the following days, several papers reported only that I had had a lousy performance in the previous year. So, I hope to be forgiven for using some of other people’s notorious mistakes as examples in this paper.

Madoff and Ponzi

One of the common mistakes made by amateur investors (and even some professionals) is to be intimidated by complicated investments and to let some kind of inferiority complex drive them to invest in businesses they do not fully understand.

Bernie Madoff was arrested in 2008 and admitted to having operated the largest Ponzi scheme in U.S. history. Named after a famous early-20th century swindler, a Ponzi scheme is a fraudulent investment operation where the operator uses fresh money coming from new investors to finance the returns promised to older investors but not earned. It can succeed only as long as money from new investors comes in faster than old investors want to cash out. Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC was founded in 1960 and the fraud may have started as early as the 1970s, which probably also makes this Ponzi scheme one of the longest-lasting in history.

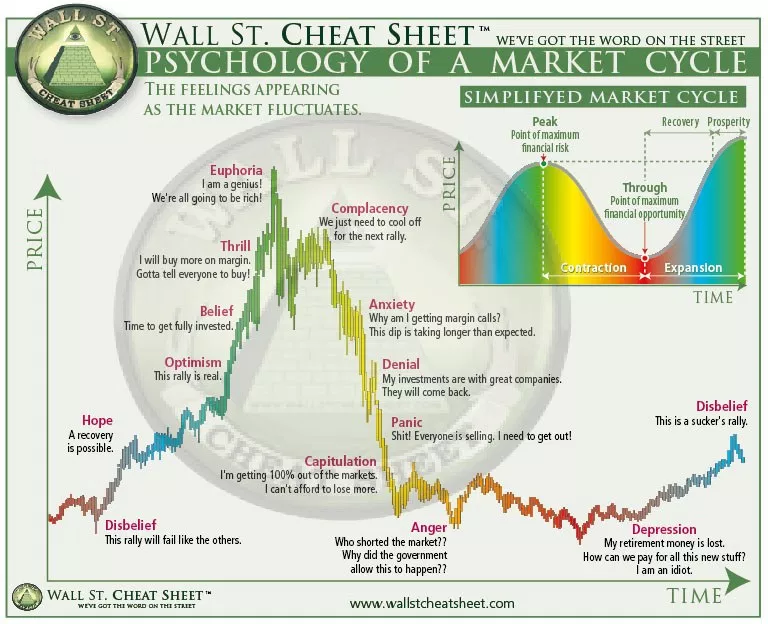

Madoff was smart enough not to promise too much: an annual return not very different from the stock market’s long-term return (10-12%). But he mostly stressed his portfolios’ very low volatility (year after year). Anyone with experience of the markets should have known that it is possible for a very good manager to exceed the net performance of the market over the long term, but not without volatility or cyclicality.

Nevertheless, many investors who were aware of that reality closed their eyes. Some chose to believe that Madoff had a magical “formula”; others thought that they belonged to a favored group of clients whose portfolios took advantage of Madoff’s market-making activities and advance knowledge of pending brokerage orders to engage in “front-running.” Of course, this would have been illegal, but when someone else takes the risk and you can claim ignorance, the border between greed and ethics becomes blurry.

Another factor assisting Madoff’s scheme was that he chose to report reasonably steady returns. A few family offices staffed with experienced investment professionals smelled something “fishy” and passed on the tempting opportunity. But many asset allocators and performance consultants, who equate volatility and risk, liked the steadiness of the reported results and failed to smell the rotten fish. At best, these consultants advised not to overweight the Madoff investment for the sake of portfolio diversification.

These professional statisticians and accountants analyze in great detail a portfolio’s performance numbers but fail to fully take into account the narrative of how and why this performance was achieved. The Madoff problem was the numbers looked good but were fabricated. No securities had ever been purchased for clients and the firm’s back office consisted of a sophisticated system for creating false reports. This situation harks back to Prof. Aswath Damodaran’s argument, summarized in my last paper: Of stories and numbers – Investing with Both Sides of the Brain (http://www.sicartassociates.com/of-stories-and-numbers/). And the main lesson of the Madoff swindle is that before you rate a performance on the numbers, you must understand how exactly that performance was achieved.

Enron: “the smartest guys in the room”

Enron was founded in 1985 by the merger of two medium-sized regional energy companies. By 2001, after a string of acquisitions and new ventures, Enron employed approximately 20,000 staff and was one of the world’s major electricity, natural gas and communication companies. Between 1995 and 2000, the company reported an increase in sales from $13 billion to $100 billion and Fortune called Enron “America’s Most Innovative Company” six years in a row. Not surprisingly, it became a very popular growth stock.

Yet it was not quite clear how the profits and balance-sheet figures had progressed over the same period. As bad news started to surface, an October 25, 2001 article in Slate.com referred to “the maddening opacity of certain aspects of Enron’s financial dealings… It’s not that someone has found, or even claimed knowledge of, some smoking gun—it’s that no one even seems certain how to look for such a thing.” Two years later, Fortune reporters Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind chronicled the Enron saga in a book, The Smartest Guys in the Room: The Amazing Rise and Scandalous Fall of Enron (2003, Penguin Group). It not only revealed more details about the continuous deceptions and the extent and complexity of the fraud perpetrated by management: it also displayed the contempt of Enron’s “smartest guys in the room” for mere bankers, accountants and financial analysts.

When one financial analyst complained, during a 2001 public conference call, that Enron was the only company that could not release a balance sheet along with its earnings statements, CEO Jeffrey Skilling replied: “Well, thank you very much, we appreciate that . . . asshole.”

During August 2000, Enron’s stock price had attained its greatest value of $90.56. By the end of 2001, as details of the scandal had begun to emerge, the stock price had fallen to almost zero and the company filed for bankruptcy.

“In the wake of Enron’s downfall, federal investigators discovered evidence of corporate arrogance, greed, and fraud of an unprecedented level.” (famous-trials.com, Prof. Douglas O. Linder)

It would be long and laborious to enumerate all of Enron’s deceptive techniques during their scandalous journey, but the following two paragraphs constitute fairly good snapshots:

“Enron used a variety of deceptive, bewildering, and fraudulent accounting practices and tactics to cover its fraud… Special Purpose Entities were created to mask significant liabilities from Enron’s financial statements. These entities made Enron seem more profitable than it actually was, and created a dangerous spiral in which, each quarter, corporate officers would have to perform more and more financial deception to create the illusion of billions of dollars in profit while the company was actually losing money. This practice increased their stock price to new levels, at which point the executives began to work on insider information and trade millions of dollars’ worth of Enron stock. The executives and insiders at Enron knew about the offshore accounts that were hiding losses for the company; however, the investors knew nothing of this.” (coursehero.com – Enron)

“Senator Phil Gramm, husband of Enron Board member Wendy Gramm and also the second largest recipient of campaign contributions from Enron, succeeded in legislating California’s energy commodity trading deregulation during December 2000… Because of Enron’s new, unregulated power auction, the company’s ‘Wholesale Services’ revenues quadrupled — from $12 billion in the first quarter of 2000 to $48.4 billion in the first quarter of 2001. After passage of the deregulation law, California had a total of 38 Stage 3 rolling blackouts declared, until federal regulators intervened during June 2001… Subsequently, Enron traders were revealed as intentionally encouraging the removal of power from the market during California’s energy crisis by encouraging suppliers to shut down plants to perform unnecessary maintenance… This scattered supply increased the price, and Enron traders were thus able to sell power at premium prices, sometimes up to a factor of 20x its normal peak value.” (www.citizen.org)

During the heydays of Enron’s popularity, under pressure from young clients, two of my former partners, both highly knowledgeable about the energy industry, went to visit the company – not just once, but twice. Their joint conclusion: “We don’t understand how they are doing it.” Thanks to the courage it took to say: “We don’t understand,” we never bought the stock.

LTCM: The Prestige of Experts and Sheepishness of Investors

Bullying financial analysts and patronizing portfolio managers is not the only way to intimidate wavering investors. Another, subtler and more sociable one is to surround oneself with presumably undisputable “experts.”

Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) was founded in 1994 by John W. Meriwether, the former vice-chairman and head of bond trading at Salomon Brothers. Members of LTCM’s board of directors included Myron S. Scholes and Robert C. Merton, who shared the 1997 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for a “new method to determine the value of derivatives.” For good measure, Meriwether had also attracted some of the star traders from Salomon Brothers to his new firm.

The LTCM team constructed models that calculated what the relative prices of securities should be across nations and asset classes. Its strategy was then to exploit deviations of actual prices from these theoretical relationships, on the assumption that market and theoretical prices would eventually converge. The company was initially involved principally in fixed income: US Treasuries, Japanese Government Bonds, UK Gilts, Italian BTPs, and Latin American debt. Because valuation discrepancies in these kinds of trades are small, LTCM used leverage to create a portfolio that could generate high returns.

LTCM began trading in February 1994, after raising just over $1 billion in capital. Investment performance in the first few years was spectacular and, at the beginning of 1998, the firm had equity of $4.7 billion. It had borrowed over $124.5 billion, for total assets of $129 billion and a debt-to-equity ratio of over 25 to 1. [It also had off-balance sheet derivative positions with the potential to control approximately $1.25 trillion of assets.] As their capital base grew, LTCM had to develop new strategies in markets outside of fixed income, and by 1998, the company had accumulated extremely large positions in areas such as merger arbitrage (betting on the outcome of mergers) and S&P 500 options

Meanwhile, the lingering effects of the 1997 Asian crisis continued to influence asset markets towards risk aversion, especially regarding those markets heavily dependent on international capital flows. In May and June 1998, returns from the fund were -6.4% and -10.1% respectively. This trend was further aggravated by Salomon Brothers’ exit from the arbitrage business in July 1998. Because the Salomon arbitrage group had been following strategies similar to those pursued by LTCM, the liquidation of the Salomon portfolio had the effect of depressing the prices of the securities owned by LTCM. Such losses further increased when the Russian government defaulted on their domestic local currency bonds in August and September 1998. A flight to quality and liquidity ensued, bidding up the prices of the most liquid and benchmark securities of which LTCM was short, and depressing the price of the less liquid securities that they owned. By the end of August, the fund had lost $1.85 billion in capital.

Finally, because the copy-cat trading desks of many major banks also held some similar trades, the divergence from fair value was increased (instead of narrowing), as these other positions were also liquidated. LTCM was forced to liquidate a number of its positions at a highly unfavorable moment and suffer further losses. In the first three weeks of September, LTCM’s equity tumbled from $2.3 billion to a mere $400 million. With liabilities still over $100 billion, this translated to an effective leverage ratio of more than 250-to-1.

Long-Term Capital Management did business with nearly everyone important on Wall Street. As its troubles intensified, bankers and authorities feared a chain reaction and catastrophic losses throughout the financial system. After a proposed buyout of the fund’s partners by Berkshire Hathaway, AIG and Goldman Sachs could not be worked out, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York organized a bailout of $3.6 billion by the major creditors to avoid a wider collapse in the financial markets.

The lesson to be drawn from the LTCM crisis is that you have not made or lost money on an investment until you sell it. Whenever a position which has been successful on paper becomes so large as to threaten market liquidity, the main question for investors who need to realize their gains or cut their losses becomes: “Sell to whom?”

Bitcoins, Genomes and The Limits of Adventure

Recently, some clients have inquired about the wisdom of investing in bitcoins. The answer is fairly simple. The bitcoin purports to be an alternative to existing currencies but so far it has only proven to be much more volatile than most currencies.

Currencies exist to facilitate the transaction of business. Let’s suppose I am a farmer selling 1000 hogs for 110 bitcoins, which is worth around US $29,700 as I write this. But in a matter of days, the volatile bitcoin could very well go from $ 2,700 today back to $1,940, where it was only two weeks ago, which means that my sale proceeds would be worth only US $21,300 – almost 30% less than I thought! Presumably, my costs (feed, farm and equipment rental, transport, labor, etc.) are all in dollars. I doubt that farmers have 30% margins to cover that almost-instant depreciation in their revenues. In fact, to my knowledge, only money laundering can withstand that kind of volatility and this may be where bitcoins belong.

It is possible that the blockchain, a type of database that underlies bitcoins and other cryptocurrencies, has many other potential applications (medical records, identity management, transaction processing, etc.) Unfortunately, it appears that, besides universities, most organizations doing the research on blockchains are either potential large users such as accounting firms, banks and insurance companies or very large corporations, so that buying their shares today for the blockchain exposure would be like buying a sandwich for the mustard.

Technologies that we do not understand, no matter how promising, offer no clear paths to financial success. On the other hand, another area we cannot claim to understand well is the biotechnology industry. And yet, in apparent contradiction to our own advice, we have invested in it.

The Human Genome Project (HGP) – an international research effort launched in 1988 by a special committee of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences — was completed in April 2003 and until then, for many, biotech’s promises remained largely in the domain of science fiction. The project sorted (sequenced) and mapped all of the genes present in members of our species, Homo sapiens, and gave us the ability, for the first time, to read nature’s complete genetic blueprint for building a human being.

Merriam-Webster defines biotechnology as the manipulation (through genetic engineering) of living organisms or their components to produce, among other products, novel pharmaceuticals. This non-traditional approach to drug development did not easily integrate into the chemically-focused research of the established pharmaceutical companies. A few pioneers like Genentech were born in the mid-1970s but the completion of the Human Genome Project thirty years later clearly launched a new era for drug research and discovery and gave birth to a new industry, on a scale that we at Sicart could not ignore.

But how could we select potential stock market winners in an industry that already counts more than 11,000 firms in the United States alone, as well as several thousand more in Europe and Asia? (2015 OECD report on biotechnology) To complicate things, most of these firms are still privately held and have no earnings nor, sometimes, revenues.

One early realization for us was that, with thousands of biologists and doctors directly employed in biotech research, the bio-geniuses were more likely to be in the lab than in Wall Street. Though it had become fashionable for financial firms to employ PhDs in biology and medicine, analysts with such diplomas were no more likely than biologists in the industry to guess which drugs would be successful.

As it turns out discovery, in fundamental research, is basically a random outcome, and no one can predict with assurance which company will discover or engineer a winning molecule. It could well be one of the smaller participants in the industry, whereas the biotech indexes tracked by most mutual funds and Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) are capitalization-weighted and trade mostly in line with the few largest companies in the sector.

Fortunately, we uncovered a biotech ETF which was almost unweighted, i.e. where most companies had a similar weight in the portfolio, regardless of their size. If a small company made an important discovery, this fund would significantly outperform traditional indexes of the sector. This was our first investment foray into biotechnology.

Later, thanks to our network of knowledgeable friends and colleagues, we identified two companies which already had some income or cash flow, and underleveraged balance sheets. These conditions would allow us to be patient while earnings rose enough, in a few years, to justify a value rationale for their purchase.

One company is developing drugs that attach themselves to strands of RNA in order to prevent them from producing disease-causing proteins. Although we have no way personally to judge the validity of that approach, we were impressed that the company had nearly 40 pipeline drugs under development, principally financed by a number of prestigious pharmaceutical partners – who presumably have some idea of what they are doing. Although the company had not yet established a steady royalty stream from products successfully commercialized by its partners, the somewhat irregular payments from various licensing fees and from reaching various research milestones had been sufficient to finance its research without the need for dilutive financings. It was easy to imagine how the success of a number of research projects, while not guaranteed, could justify in a few years a valuation well beyond today’s.

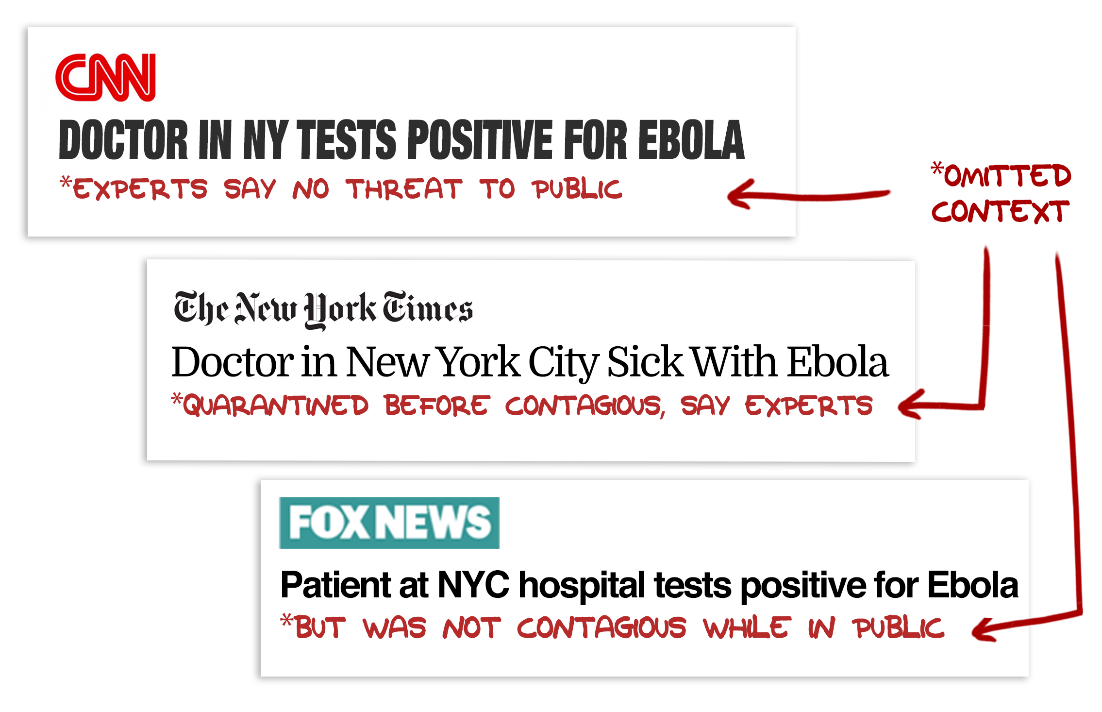

The other company’s specialty is making small, cheap and fast diagnostic devices to detect infections such as HIV, Hepatitis C, Ebola, and Zika. Tests already in use allow for financial independence and future growth without costly outside financing. But, as the biotech revolution progresses, the pricing of expensive cures will eventually drop and governments will likely decide to eradicate some major global plagues. This will create new growth opportunities for wide-scale genetic testing. Hence, this company promises to be a safe, derivative way to benefit from the emerging golden age of biotech without betting on specific drug developments.

Conclusion

Traditional value investors cannot completely ignore the emergence of new industries and activities that are less tangible but knowledge-heavy. On the other hand, these new activities, no matter how promising on a macroeconomic level, will not necessarily engender major stock market winners beyond early speculative flurries. Imagination, selectivity and persistence are all necessary to the discovery of good investments. This is why our quest continues…

François Sicart (August 4, 2017)

Disclosure:

This article is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.

NYSE “FANG+” INDEX *

NYSE “FANG+” INDEX * S&P 500 INDEX **

S&P 500 INDEX **